Our ethical obligation in research and practice

In this first part of two articles, I will provide the background to equality, equity, diversity and inclusion (EEDI) issues in psychological research and explain why this matters and how it could impact therapeutic practice. The second article in the next issue of ETQ will be concerned with the practicalities of introducing an EEDI framework into psychological research.

Positionality statement

I was born and brought up in South London. My grandparents were born in India and my parents in East Africa, from where they moved to the UK. Like many of my generation, I grew up in a working-class home and attended state schools. I grew up with others from minoritised groups.

I identify as a heterosexual, cisgender woman, educated to postgraduate level, able-bodied, perimenopausal, multilingual, English-speaking individual who is neurodiverse and has her own learning differences.

I am not a researcher but have engaged in and conducted research at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels and have noticed barriers in my own research and professional journey. I am the co-founder of the Walden Model, supporting members in the community to provide an attachment-based therapeutic family on a long-term basis. Community psychology is of great importance to me, where I work with those who have been underserved in statutory and often voluntary services too.

I am a counselling psychologist and EMDR consultant supervisor working with adolescents and adults in education, the community and with charities. I am a Board member and Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Committee chairperson at the EMDR UK Association. I work with the Association to infuse equality, equity, diversity and inclusion (EEDI) into practice, where voices and people are not ignored but are heard and responded to.

The tight tapestry we continue to weave

Almost daily, we see and hear much through various media about difference, depending on what the calendar is highlighting, e.g. autism awareness, breast cancer, men’s health, mental health awareness, South Asian Heritage Month and this year Rare Disease Day (29 February). The list continually grows. October marked Black History Month and World Menopause Awareness Month. On 18 October, it was not only World Menopause Day but Anti-Slavery Day too. Those who are part of the global majority (Campbell-Stephens (2009) refers to this as people who are Black, Asian, Brown, dual-heritage, indigenous to the global south, and those who have been racialised as ‘ethnic minorities’) are among those who are particularly highlighted in the month of October as I write this article.

The global majority represents approximately 80% of the world’s population (Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association). In addition, about 50% of the global population is female (Trading Economics, 2023). The Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) is an independent public body that receives funding from the government and provides “free and impartial advice to employers, employees and their representatives on employment rights, best practices and policies and resolving workplace conflict.” It points out that although “the menopause is not a specific protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010, if an employee or worker is put at a disadvantage and treated less favourably because of their menopause symptoms, this could be discrimination, if related to a protected characteristic.” This has recently had more coverage in the national news leading up to International Women’s Day (8 March).

February celebrates LGBTQ+ history and it is important to note that menopause may be experienced by some transgender men, non-binary people, intersex people and people with variations in sex characteristics. Females also make up much of the psychotherapy profession and the EMDR UK Association membership. There is, of course, a discussion, for another time, about the barriers faced by men entering these professions too.

Law, directives, and declarations

The first of October is the anniversary of the Equality Act 2010, which formally recognised that discriminating against anyone with a protected characteristic was unlawful. This was only 14 years ago! Furthermore, the Modern Slavery Act (2015) does not apply to any offences committed before 31 July 2015. This is not surprising, as the compensation paid to British slave owners in 1835 due to the abolition of slavery was paid off by British taxpayers only nine years ago in 2015 (Reid, 2021).

Human and social injustices continue to happen today and have done so over centuries through oppressive practice at societal, organisational, institutional, group and individual levels. Amnesty International continues its work to uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and “work to end human injustice” due to overt “human rights abuses happening now.”

It is unlawful to engage in positive discrimination, but maybe taking positive action here is needed. The Equality Act 2010 lists nine protected characteristics (see figure 1) that cannot be discriminated against, yet it is often done so by omission and/or by ignoring that they exist! Is this not prejudicial and discriminatory in itself?

| Age |

| Disability (seen and unseen) |

| Gender reassignment |

| Marriage and civil partnership |

| Pregnancy and maternity |

| Race (ethnicity and culture) |

| Religion or belief (spirituality) |

| Sex |

| Sexual orientation |

Another area of consideration may include socioeconomic status. While this is not a protected characteristic, it is an area that is underrepresented and often unnoticed.

Equality, equity, diversity and inclusion

The EMDR Association UK refers to EEDI in their EDI policy as follows:

| Equality | Refers to everybody having the same opportunities and is treated with the same respect, rights and provided with the same opportunities. |

| Equity | Refers to everyone being treated fairly and making reasonable adjustments, allowing fair and impartial practice. |

| Diversity | Refers to valuing and involving individuals for the different perspectives they have to offer and celebrating difference. |

| Inclusion | Ensures an equitable approach where everybody has a voice that is heard and a means to participate, which may involve widening access and making reasonable adjustments to our usual processes, in addition to taking into consideration any mitigating circumstances. |

Intersectionality

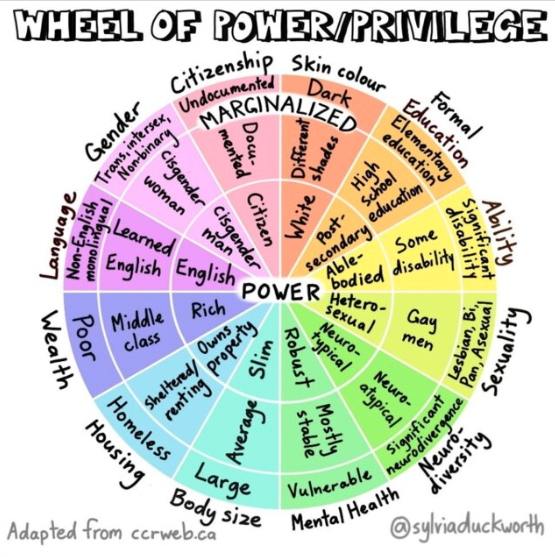

Kimberly Crenshaw (1989) coined the term ‘intersectionality’ and explicitly highlighted the multiple oppressions faced by those with intersectional experiences and characteristics, which include but are not limited to our physical, psychological, social, religious, familial, financial and socioeconomic status. This undeniably perpetuates the socially inflicted trauma faced by individuals and groups in society. Below is a diagram created by Duckworth, The Wheel of Power/ Privilege (image 1), highlighting the spectrum of and relationship between power, privilege and marginalisation based on one’s intersections of experiences and characteristics.

This simplistic diagram highlights areas of oppression/marginalisation and power/privilege. It does not provide an exhaustive list of intersectional characteristics and areas of marginalisation. Not everyone will agree with all the characteristics suggested, but the wheel does demonstrate the spectrum of intersectionality and multiple grounds for oppression (the foundations of which may be based on bias), impacting an individual’s lived experience. There are, of course, other diagrams highlighting the spectrum of intersectionality, some of which include erasure and ignored vulnerabilities (experiences/characteristics).

Lightbody (2017), in their work regarding promoting equality in community engagement, expresses that those who have previously been ‘hard to reach’ are acknowledged as those who have also been ‘easy to ignore’ due to:

- Their complex situations

- Little understanding from the government, organisation and programmes

- Difficulty forming solutions.

This contributes to the maintenance of socially inflicted trauma through inequalities experienced by the most vulnerable in society, perhaps because they are too different from those in positions of power and there is little desire to understand their complexity, context and frame of reference.

Changing the narrative

It is disappointing that when the ‘awareness’ day or month is over, we all fall quiet again. While we continue to live ‘with diversity’ rather than ‘within diversity’ (Khan, 2023), it is so easily ignored. Khan (2023) observes that everyone is in a position of power and privilege, and therefore diversity is something everyone experiences. Acknowledging that we are all different (which is the one thing we have in common) allows the overt and conscious consideration of an individual’s intersectional spectrum. Each person lives their narrative; they do not stop when the awareness day or month does. Issues in the spotlight each month cannot be confined to that space but need to be considered continually in research, practice, and interactions. This involves, if one chooses, engaging in action both individually and collectively, being changemakers rather than bystanders, being ‘anti’ rather than ‘non’ oppressive.

There will always be blind spots for individuals and groups, but it is no longer acceptable for anyone to stay quiet and defuse responsibilities that perpetuate oppressive practices. There is an obligation to embed the principles of EEDI into all aspects of work. In turn, there is a responsibility to change the narrative of oppressive practices in research and practice. Unfortunately, advocating for much of EEDI is left to those who are from marginalised groups. There is a history of dissonance reduction (acting to maintain consistent beliefs) (BPS, 2021) and cognitive dissonance (inconsistency related to thoughts, beliefs, and actions that can lead to an internal mental conflict) (Morris, 2023).This is not only in relation to the transatlantic slave trade, as researched by DeGruy (2017) in their work regarding posttraumatic slave syndrome (PTSS), but also the inhumane behaviours of others and events that have occurred and continue to happen today. This oppressive practice also affects those who appear to be different from the ‘norm’ of the local majority.

Ethical reasoning

Ethical reasoning is often influenced by several biases. Maintaining and developing awareness of such biases is important when trying to think through ethical, research and therapeutic practice challenges. These considerations may include, but are not limited to:

- Salience (how readily something comes to mind)

- Confirmation bias (the human tendency to look for evidence that confirms their belief and to ignore other evidence)

- Loss aversion (behaviour to avoid loss)

- Beliefs about disclosure (tendency to be more honest when they believe their actions will be known by others)

- Dissonance reduction (acting to maintain consistent beliefs)

- Implicit bias (bias that occurs automatically and unintentionally but nevertheless affects judgements, decisions, and behaviours).

(BPS, Code of Ethics and Conduct, 2021).

Within the area of psychology, it is acknowledged that all humans have biases, and the aim is to reduce the impact of these biases and develop skills to work effectively with those from diverse communities and underrepresented groups (Banaji & Greenwald, 2013, as cited in APA EDI Framework). The individuals or organisations conducting the research and how that might cause study bias also need to be considered. Study bias occurs if the study population does not closely represent a target population due to errors in study design or implementation (Popovic et al, 2023).

Researchers and consumers of research, which includes therapeutic practitioners, are encouraged to consider these factors in their own decision-making and heuristic journey in their learning and practice development. This will be challenging as one actively dares to differ from the Eurocentric norms. It is essential to recognise and challenge biases that influence research and practice processes. Investing time and resources into bias reflection and training through dialogue (rather than online modules) may help ensure that the researcher and their teams can approach the study with fewer (and known) biases, prejudice and discrimination.

Decolonisation

Sofia Akel, the race equality lead in higher education at London Metropolitan University, explains that primary and secondary socialisation is heavily influenced by “formal and informal agents of social control,” which include “the law, religion, our families, our neighbourhoods and public opinion… reinforced through [the] education [system]… [as it] is firmly rooted in colonial epistemology, which centres and upholds the British Empire and the forms that it takes today. [This includes] a retelling of the history of empire that speaks only to its ‘successes,’ while omitting its evils, the voices of the oppressed, and the lasting legacy of imperialism today” (Akel, 2020). Decolonising research and practice requires systemic change from the first time one engages in research (even for children as early as key stages two and three), as well as at degree and postgraduate level.

Each person has their own narrative (which includes both lived and generational experiences) that impacts their understanding, interpretation, relationships and functioning in society. Being open and mindful to learning about difference and engaging in challenging conversations, as well as being willing to lower defences may facilitate the work of decolonising research and practice. This is essential for further inclusion, growth and development.

Many higher education institutions attempt to tackle what is meant by decolonising. Akel (2020) shares that “decolonisation typically refers to the withdrawal of political, military and governmental rule of a colonised land by its invaders. Decolonising… is often understood as the process in which we rethink, reframe and reconstruct the curricula and research that preserve the Europe-centred, colonial lens. It should not be mistaken for ‘diversification,’ as diversity can still exist within this western bias… Decolonisation goes further and deeper in challenging the institutional hierarchy and monopoly on knowledge, moving out of a western framework.”

Most major core professional training and accrediting psychotherapeutic and health organisations are actively attempting to make changes in their training material to acknowledge diversity and accessibility based on the trainee’s intersectional experiences. Of course, reasonable adjustments are also made in most organisations on a case-by-case basis, in line with equality, equity, diversity, and inclusion (EEDI) policies and the Equality Act 2010. Going ‘further and deeper’ (Akel, 2020) by way of engaging in the process of decolonisation, Abbas & Farooq (2022) call for ‘Whiteness, power, racism and colonisation’ to be a core and compulsory component of psychologist training, as there is significant evidence that scientific racism exists (e.g., in neuropsychology). This could be extended to the psychotherapeutic profession, which would benefit from continual training and reflection on EEDI in practice and research.

Consumers of research

We are all accountable for EEDI in practice and research; it is not a one-person job or for a committee to consider EEDI and drive through change; rather, it is a collective responsibility, as individuals and as part of the group(s).

As consumers of research and delegates attending CPD training events relating to the dissemination of research and applications in evidence-based practice, there is an obligation to challenge and consider EEDI in practice. Some considerations may include, but are not limited to:

- Engaging in constructive feedback to event organisers to question EEDI in events/training, which would enable active reflection and development in future events and critical consideration in disseminating research outcomes

- Acknowledging and carefully exploring one’s biases and narratives (lived and generational experiences) and how they impact one’s understanding, interpretations and application of research into practice. Being transparent about our own positionality and biases will allow us to learn more and strive towards the ethos of decolonising our own oppressive practices

- Engage in critical reflection on the research we engage in and apply in practice, while honouring our clients, our own intersectional experiences and the power, privilege, oppression and marginalisation that come with it

- Understanding the historical and collective trauma of specific ethnic groups, those with disabilities, physical and mental health conditions, neurodiversity and learning difference, allows us to take an inclusive and holistic approach to understanding participants and clients

- Putting research into practice when co-formulating/constructing and treatment planning with clients. Enabling opportunities to explore and acknowledge difference in society/cultures and the therapy room

- Santos (2019) provides an ‘EMDR case formulation tool’ to develop an understanding of the client’s presentation, which can support treatment planning. Co-formulating with clients (where developmentally appropriate) and exploring their generational and intergenerational experiences and narratives provides a rich understanding of the client’s world. Working collaboratively with the client to learn about their narrative now, while engaging in research to develop an understanding of the client’s context is indispensable. Adding intergenerational narratives and intersectionality to the formulation tool can assist with the case conceptualisation of the client’s presentations and therefore inform the treatment plan. This might include, but is not limited to, identifying traumas and resources through generations, and assisting the adaptive information processing in working across cultures and with minoritised groups

- Understanding how the narrative of the researcher, client, psychotherapist, supervisor and societal context impact responding to the client in the psychotherapy room. Consider how these narratives impact the understanding, attunement and treatment planning to meet the client’s need.

These suggestions equally apply when considering our own therapeutic practice. Additionally, we can engage with other therapists and share our own diversity through peer and group supervision. This can reveal varied experiences, perspectives, and skills. Such opportunities can be used to learn and develop an understanding of other perspectives and our own.

We can notice where there is an attempt to fit a therapeutic model, theory or research outcome to a client’s presenting concerns rather than considering their intersectional and intergenerational context and experiences. Finally, we can become aware of how culturally sensitive we are to our clients and honour their needs while recognising our own intersectional and intergenerational context.

Conclusion

Oppressive practice is being maintained, and research outcomes (perhaps lacking reliability and validity) continue to inform many therapeutic interventions. In his introductory message for the 25th anniversary conference for EMDR Europe 2024, Olivier Piedfort-Marin (President of the EMDR Europe Association) says that “’Pathways to Peace with EMDR’ relates also to something very dear to Francine Shapiro. She believed that EMDR therapy could reduce and prevent the transfer of trauma from one generation to the next, and in doing so, building trust between people and nations and helping to create the conditions for lasting peace. This is what EMDR therapists are doing every day, directly or indirectly, all over Europe and all over the world.”

In my opinion, this speaks to, amongst other things, respect, anti-discriminatory practice, equality, and not perpetuating the marginalisation (and trauma) of vulnerable and minoritised groups through research and dissemination of research through the daily practice of EMDR therapists. Ultimately, as EMDR therapists and consumers of research, we need to consider how we might be continuing to add to the tight tapestry of oppressive practice that has developed over centuries and which continues to marginalise in the present. It is vital that, as consumers of research, we build an awareness and understanding of how the history of psychology has shaped current evidence-based practice, practice-based evidence and therapeutic intervention. Further, we should acknowledge that therapeutic practitioners can enable the unethical dissemination of research. Therefore, a responsibility to engage in critical thinking, learning and tailored interventions to attune to the client’s holistic context rather than applying a Eurocentric lens (and research) to understanding their intersectional experiences is essential.

References

Abbas. S., & Farooq. R. (2022). Is it time to decolonise neuropsychology? Critical reflections on colonial structures, neuropsychology and the role of clinical psychologists. Clinical Psychology Forum, 359.

ACAS. (n.d.). Retrieved 6 March 2024, from https://www.acas.org.uk

Angai, C., & Gildea, B. (2024). Power and the unWEIRDification of behavioural science. Intellectual forum. Jesus College, Cambridge. Retrieved 28 February 2024, from https://www.jesus.cam.ac.uk/events/power-and-unweirdification-behavioural-science

Akel, S. (2020). What decolonising the curriculum really means. EachOther. Retrieved 23 March 2024, from https://eachother.org.uk/decolonising-the-curriculum-what-it-really-means/

APA. (2021). Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Framework. https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/framework.pdf

APA. (n.d.). Inclusive language guidelines. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/language-guidelines.pdf

Arellano, L. (2022). Questioning the science: How quantitative methodologies perpetuate inequity in higher education. Education Sciences, 12(2), 116. https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7102/12/2/116

Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2013). [Cite to APA EDI Framework]

BPS. (2021). Code of Ethics and Conduct. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://www.bps.org.uk/guideline/code-ethics-and-conduct

Campbell-Stephens, R. (2009). Investing in diversity: Changing the face (and the heart) of educational leadership, School Leadership and Management, 29(3).

Center for Teaching, Learning and Mentoring Knowledge Base. (n.d.). Wheel of privilege and power. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://kb.wisc.edu/instructional-resources/page.php?id=119380

Cobanoglu, A. (2023). What is QuantCrit, and Why It is Critical for Education Research? Education Studies. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://educationstudies.yale.edu/event/what-quantcrit-and-why-it-critical-education-research#:~:text=The%20aim%20of%20QuantCrit%20(Quantitative,considering%20systemic%20inequities%20in%20society.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8).

DeGruy, J. (2017). Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome, Revised Edition: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. Joy DeGruy Publications Inc.

EMDR UK Association. (n.d.). EDI Policy. Retrieved 07 March 2024, from https://emdrassociation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/EDI-Policy-Jan-2023.pdf

Equality Act 2010. (n.d.). Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

EU directives. (n.d.). Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://commission.europa.eu/aid-development-cooperation-fundamental-rights/your-rights-eu/know-your-rights/equality/non-discrimination_en

Francis, D., & Scott, J. (2023). Racial equity and decolonisation within the DClinPsy: How far have we come and where are we going? Trainee clinical psychologists’ perspectives of the curriculum and research practices. Clinical Psychology Forum, 366.

GOV.UK. (2023). Ethnicity facts and figures. Male and female populations. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/demographics/male-and-female-populations/latest

Holmes, A. G. D. (2020). Researcher positionality: A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research – A new research guide. International Journal of Education, 8(4).

Immigration Law Practitioners Association. (n.d.). Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://ilpa.org.uk/people-of-the-global-majority/

Islam, N., Rahim, M., Wang, M., Jameel, L., Rosebert, C., Snell, T., Randall, J., Ruth, D., Parekh, H., Kaur, M., Lam, C., Mudie., S and Cream., P. (2022). Equity, diversity and inclusion: Context and strategy for clinical psychology (Version 1). ACP-UK.

Katsampa, D. (2023). ‘Striving and thriving together’: Reflections from carrying out a programme-related project on decolonising research in clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology Forum, DCP, 366.

Khan, M. (2023). Working within diversity. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lightbody, R. (2017). “Hard to reach” or “easy to ignore”: Promoting equality in community engagement. What works for Scotland.

Modern Slavery Act 2015. (n.d.). Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/30/contents/enacted

Morris, C. (2023). When two roles clash. The Psychologist. January 2023.

Piedfort-Marin, O. (2024) https://emdr24.com/

Popovic A, Huecker MR. Study Bias. [Updated 2023 Jun 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574513/

Reid, N. (2021) The Good Ally: A guided anti-racism journey from bystander to changemaker. HarperCollins Publishers.

Roßler, D. C., Lötters, S., & Da Fonte, L. F. M. (2020). Author declaration: have you considered equity, diversity and inclusion? Nature, 584(7822), 525. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A633468925/AONE?u=anon~c285e8eb&sid=googleScholar&xid=72b8313a

Ruycki, S.M., & Ahmed, S.B. (2022). Equity, diversity and inclusion are foundational research skills. Nature Human Behaviour, 6. Retrieved from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-022-01406-7

Santoro, H. (2023) The push for more equitable research is changing the field: Psychologists are challenging traditional thinking about their research, including how it is conducted and who it includes. Monitor on Psychology, 54(1). American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/01/trends-inclusivity-psychological-research

Santos, I. (2019). EMDR case formulation tool. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 13(3).

Trading Economics. (2023). World – Population, Female (% Of Total) – 2023 Data 2024 Forecast 1960-2022 Historical. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://tradingeconomics.com/world/population-female-percent-of-total-wb-data.html

United Nations. (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Retrieved 06 March 2024, from https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights