Regulars

What is unique about EMDR supervision?

Robin Logie shares his thoughts on EMDR supervision.

Winter 2024

Mother Nature’s great trick was to drop the human brain into the world, essentially half-baked, and then we allow our environments to wire up the rest of us, so your local language, your culture, your belief system, all that stuff you absorb… Humans have taken over every spot on the planet because we’re so flexible, so flexibly intelligent.

David Eagleman, The Infinite Monkey Cage, BBC Radio 4, 14.07.20.

As ever, I am attempting to make this column appropriate reading for all EMDR therapists, as consumers of supervision as well as purveyors of supervision.

This month, I plan to focus on the ‘educating’ function of EMDR supervision. Just to recap, I have called the three basic functions of supervision (with the older terms in brackets) as follows:

The three Es, as I like to call them.

You may recall that I was going to cover the educating function in my last column, but, distracted by the England Women’s World Cup team and their wonderful manager, I got carried away talking about the enabling function. So, back to educating…

I think it could be really useful to start by taking a good look at the theory of learning and how we can understand this in relation to our own adaptive information processing (AIP) model for EMDR. In fact, the AIP model is a kind of theory of learning, so it might be useful to see how this relates to how we learn to become EMDR therapists. My book goes into more detail about theories of learning in relation to EMDR supervision, but let’s just focus on one of these, which I have found to be particularly useful.

For me, as an undergraduate in the 1970s, ‘learning theory’ was all about classical and operant conditioning. This was quite relevant when predicting the behaviour of experimental rats in cages but not so useful in understanding how an EMDR therapist might develop their skills through supervision. So, when I started writing my book, I revisited theories about learning, was fascinated by the ideas of Kolb, and acquired his basic text on ‘experiential learning’ (Kolb, 2015).

As I started to work my way through this book, I first tried to make sense of what Kolb was saying, putting it into my own words and understanding it in relation to what I already think is happening when people are trained and supervised in EMDR therapy. I started to think about what is taking place, for example, when an experienced CBT therapist first observes a session of EMDR therapy during their part 1 training and how they try to assimilate this with what they already understand about therapy. For example, they might be wondering how cognitive change could occur in the absence of Socratic questioning.

Kolb talks of learning as an interaction between the person and their environment and regards learning as the major process of human adaptation. He makes no mention of attachment theory, but clearly, the type of attachment style that an infant develops at an early age reflects their best attempts at adapting to the world in which they find themselves to maximise their safety (Bowlby, 1969).

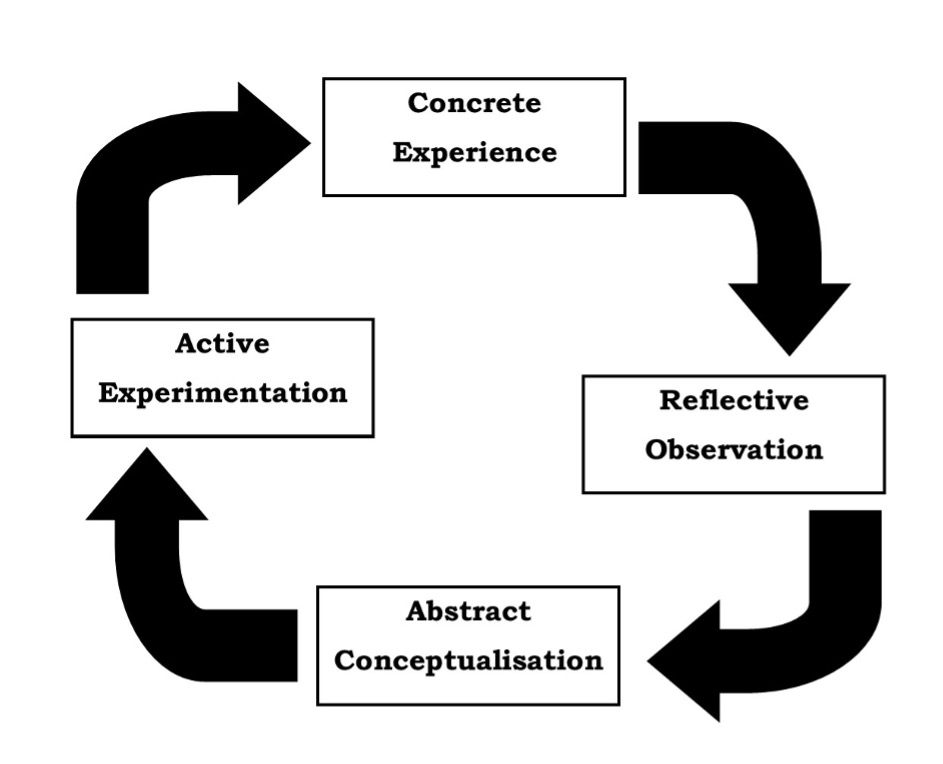

Kolb refers to the work of Piaget (1970), who posited that the key to learning lay in the mutual interaction of the process of ‘accommodation’ of concepts or schemas to experiences in the world and the process of ‘assimilation’ of events and experiences from the world into existing concepts and schemas. Kolb describes the experiential ‘learning cycle,’ where he defines learning as “the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (Kolb, 2015, p. 51). He describes knowledge as resulting from the combination of taking in information and then transforming the experience. The latter is the way individuals interpret and act on the information they have taken in. He describes four learning modes as follows:

Immediate or concrete experiences are the basis for observations and reflections. These reflections are assimilated and distilled into abstract concepts from which new implications for action can be drawn. These implications can be actively tested and serve as guides in creating new experiences.

(Kolb, 2015, p. 51).

Figure 1 below summarises this.

Does any of this sound familiar? Well, to my mind, it is basically an elaboration of the AIP model, which describes how we process new experiences and assimilate them into our existing understanding of ourselves and the world. When we are able to adaptively process an experience in this way, “we learn something about ourselves and other people, we better understand past situations, and we are better able to handle similar situations in the future” (Shapiro, 2018, p. 27). So, with Kolb’s help, we can elaborate on the AIP model and provide more detail about the process by which this learning and adaptation happens. This is particularly relevant in understanding what occurs when someone is training in a new therapy such as EMDR.

Let us think about what is happening to me, as the trainee, on my first day of basic EMDR training and being told about the AIP model and how this relates to the EMDR standard protocol. It starts with my concrete experience of what the trainer is presenting. I will then reflect (reflective observation) on what I have been told and start to assimilate this with what I already understand about psychological functioning and my own experience as a therapist. I will then move on to creating some new abstract concepts (abstract conceptualisation) as a result of this assimilation, perhaps helped by questions I may ask of the trainer. Finally, I will experience using EMDR therapy myself in the training (active experimentation) either as a client or as a therapist, which itself is a further concrete experience. And so, the cycle goes on.

Building on Kolb’s learning cycle, Honey & Mumford (1992) described four learning styles as follows:

When one thinks specifically about how this applies to EMDR supervision, there are some important considerations. If I am a pragmatist, I am likely to have little difficulty getting stuck into doing EMDR processing. However, I may need more help with case conceptualisation, standing back and reflecting on what is happening with my client. If I am a theorist, I will need more help with being able to act, experience and get going with phase 4 processing.

Fear is often the reason why particular therapists become stuck in a particular learning style. Over many years, I will have developed my learning style as my own safe place when I feel under pressure. Kolb (2015) describes these as non-learning postures. Learning a new therapy, such as EMDR, may drive me back into my safe place. Pepper (1942) shows that the extreme positions of dogmatism and absolute scepticism are inadequate foundations for learning. He proposes that partial scepticism is more conducive to learning.

Before we trained as EMDR therapists, we all started as therapists in some other therapeutic modality. When learning about the EMDR protocol in supervision, our supervisor must always acknowledge where we are coming from and start from there. For example, when teaching about therapeutic interweaves, I have had comments from CBT therapists that it sounds rather like CBT, to which I will reply, “An interweave is like a little bit of CBT that we are throwing in here, but the difference is that we then stay out of the way and trust the process and only use another interweave if they get stuck again.”

As therapists, we are often scared of making mistakes, perhaps particularly in EMDR, when many of us secretly suspect that we are getting it all wrong. I confess that, even as a senior trainer with over 25 years of experience using EMDR, I sometimes secretly worry that I am doing it wrong and will get found out! So, this is an important issue to address.

“Success is a lousy teacher,” said Bill Gates. In my training and supervision, I always emphasise that, when we make a mistake, we learn more than when we get things right the first time. I also quote the conductor of my choir, who says that when you get to a tricky bit that you are unsure about, “Sing up so I can hear your mistakes and help to correct you.” We never fail as therapists; we just learn more about our clients and the therapy we are using. If something goes wrong, it is new information, not a disaster. In fact, there is some experimental evidence to indicate that making deliberate errors in a learning task will enhance learning (Wong & Lim, 2022).

As a supervisor, I try to model openness about mistakes I have made, and, in my own case, I have plenty to choose from! Experimental studies have shown that the greater the perceived similarity, the greater the imitation. My supervisees appreciate hearing stories about my own work in order to illustrate a point I wish to make, and as one supervisee said, “I particularly like to hear about when you have messed up!”

One of the unique aspects of EMDR supervision is how it is closely linked to basic training. At a very illuminating day-long workshop by Bruce Perry at the EMDR Europe conference in The Hague in 2016 (Perry, 2016), I learned an important lesson about the nature of how we learn. However excellent your teaching is, students will not absorb all the information because, while they are processing and assimilating one piece of information, they will not have the capacity to take in what you tell them next. This accords with the AIP model and the idea that we do not just make a video recording of our experience, but we assimilate it with our existing experience and knowledge. In a training situation where we are learning about EMDR for the first time, we will need to make sense of what we are learning by assimilating it with how we already understand psychological functioning and therapy. Therefore, even a supervisee who is intelligent, attentive, and diligent and has trained with the best trainer will still have gaps in their knowledge, which the supervisor will need to find as they go along.

So, let’s finish by trying to summarise what all of this means for you as an EMDR supervisee or supervisor. Basically, the educational function of supervision is about learning the EMDR protocol and developing the necessary knowledge to become a more effective therapist. To benefit from supervision, I need to be open and honest about the difficulties I am having with my clients and, together with my supervisor, work out how best I can learn. Sometimes my supervisor will just need to tell me something that I have not recalled from my training or some nifty protocol or technique that I was unaware of or didn’t really understand from my training. But sometimes it is a more fundamental lesson that I may need to learn about EMDR, and my supervisor may help me by telling a story about where they went wrong in the past and then realised what they needed to do.

As a supervisor, when we have finished discussing a particular client, I will ask, “How does that feel now?” rather than “Do you know what to do now?” This is because my supervisee is likely to have learned something much more fundamental if there is an emotional shift coupled with a cognitive shift, rather in the way that positive cognition is not just a belief but also has an attached emotional charge. My supervisee’s apparent initial discomfort with their, as yet unresolved, supervision question will give way to an expression of relief as if to say “aha!” and, if I am lucky, an expression of gratitude.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, volume 1: Attachment. London: Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Honey, P., & Mumford, A. (1992). The manual of learning styles (Vol. 3). Maidenhead, UK: Peter Honey.

Kolb, D. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Pepper, S. C. (1942). World hypotheses: A study in evidence (Vol. 31): London: Univ of California Press.

Perry, B. (2016). Introduction to the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Paper presented at the 17th European EMDR conference, The Hague.

Piaget, J. (1970). The place of the sciences of man in the system of science. New York: Harper Torchbooks.

Proctor, B. (1988). Supervision: a co-operative exercise in accountability. In M. Marken & M. Payne (Eds.), Enabling and ensuring. Leicester: National Youth Bureau and Council for Education and Training in Youth and Community Work.

Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Publications.

Wong, S. S. H., & Lim, S. W. H. (2022). The derring effect: Deliberate errors enhance learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151 (1), 25.

Regulars

Robin Logie shares his thoughts on EMDR supervision.

Supervision

In his regular column, Robin Logie reveals his interest in women's football and shows how the compassionate leadership of The Lionesses' coach can be an example for EMDR supervisors.