Evidence to support EMDR as a primary intervention in adults with childhood trauma: Results of a service evaluation

There is overwhelming evidence that neglect and abuse experienced in early life negatively affects the trajectories of individuals’ lives and of those around them. Not only is the potential for meaningful, productive lives marred, but the aggregate cost to nations in physical and mental healthcare, social care, judicial care, law enforcement, and education is extremely high.

The aim of this pilot service was to offer a psychological service to adults to specifically address the long-term effects of childhood trauma. A time-limited, 20-session service using EMDR as the primary intervention was provided. PTSD symptoms were measured using a standardised questionnaire before and after the intervention and at 1-month and 6-month follow-up. Qualitative data was also collected.

There was a highly statistically significant reduction in PTSD scores immediately after treatment, at 1-month and 6-month follow up. 100% of service users reported improvements and no one dropped out of treatment. This demonstrates the effectiveness and acceptability of this service to this user group making it promising for further research and development. Qualitative reports from service users provided deeper insights into the emotional and psychological changes experienced by them.

Poor mental health causes enormous direct as well as indirect costs to society through physical health care, lost income and productivity, social care, crime, education, justice and correctional facilities. The results of this service evaluation suggest that the cost benefits of assessing for and treating the root causes, rather than just the presenting symptoms, might extend beyond the immediate health care setting.

Introduction

To live in nations graced with national health and other care services is an uncommon privilege. However, the reality of the ever-swelling demand, growing complexity, and shrinking budgets increasingly renders the cost-effective provision of such services an increasingly elusive pursuit (CGI Group Inc., 2014). Whilst the beneficence of such systems aids the welfare of its citizens in innumerable ways, the costs of maintaining such public services and proving their cost-effectiveness in increasingly challenging fiscal environments is more critical than ever, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic.

In these fiscally restrained times, where there are many deserving demands on public money, the demand for mental health support is rising, further increasing the strain on economies. The rise in demand for mental health support since the pandemic has understandably increased waiting lists in the UK (Gregory, 2022). The need for improved mental health services has been highlighted (Office for National Statistics, 2020) as has the call for savings by governments and practitioners (Davenport et al., 2020).

Poor mental health causes enormous indirect costs to society through physical health care (Firth et al., 2019), lost income and productivity (Latoo et al., 2021), social care (Knapp & Wong, 2020), the judicial system (Scott et al., 2001), and education (Wykes et al., 2021); so it follows that improved mental health would result in savings not just in the mental health service, but in these sectors too. Additionally, an increase in individuals’ economic productivity because of improved mental health could simultaneously reduce financial strain as well as add to the national bottom line.

The link between adverse individual experiences and national economics

Perhaps the study that made the most impressive link between adverse individual experiences, mental health, and the economic burden on nations resulting from this phenomenon, was that undertaken by Kaiser Permanente and the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the mid-90s (Felitti & Anda, 1997). Using data from 17,000 people, it demonstrated that physical, social, and mental ill-health were not just transient conditions, but a persistent reality through the lifespans of individuals who had experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Physical and/or emotional neglect; physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; household substance abuse; household mental illness; witnessing a caregiver being treated violently; parental separation or divorce and the imprisonment of a household member, all contributed to these outcomes (American Academy of Paediatrics, 2014). Those who experienced four or more such ACEs compared to those who had experienced none showed a four- to twelve-fold increase in health risk for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempt; a two- to four-fold increase in smoking and poor self-rated health; and an approximately one-and-a-half-fold increase in physical inactivity and severe obesity. They were also found to be more likely to engage in behaviours detrimental to their health in adolescence and adulthood, and to have experienced or perpetrated violence and spent time in prison (Connected for Life, 2017). This demonstrates that the cost of ACEs falls not only to individuals, but to a nation’s social, judicial, law enforcement, physical and mental health sectors. According to Burke Harris (2014), childhood trauma in high doses affects brain development, the immune system, the endocrine system, and even the way DNA is read and transcribed. Those exposed to very high levels have triple the lifetime risk of heart disease and lung cancer. Sadly, similar findings are mirrored in England (Bellis et al., 2014a), Wales (Public Health Wales, 2015), and in young adults in eight eastern European countries (Bellis et al., 2014b).

While the Kaiser Permanente study found a link between these specific factors and outcomes, consensus amongst researchers of the connection between human neurology, physiology, emotion, cognition, self-regulation, perception, and relational functioning through the lifespan of human development has led to greater clarity of the depth of, and the sometimes intractable impact of poor early attachment relationships on immediate as well as long-term human functioning (Lautarescu, Craig, & Glover, 2020; Schore, 2009; Bergmann, 2020). The greatest disturbance is experienced by those who have a history of chronic severe developmental trauma (Karam et al., 2014). With evidence from different disciplines converging, it is becoming increasingly accepted that many psychiatric conditions have their root in early developmental trauma (Schore, 1996, 2003).

The pilot service

An awareness that the needs of adults who had experienced childhood trauma (single events, as well as chronic relational trauma) were not currently being effectively met by mental health services, culminated in a decision between local government and the National Health Service to offer a pilot bespoke psychology service to them. The pilot service was designed within the constraints of the tension between clinical need and limited resources, requiring, a time-limited, results-driven approach. It was offered to adults who had experienced childhood trauma and were experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms at the time of referral and treatment. Those who had received treatment from England’s Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) primary care service but kept returning due to recurrent symptoms and had childhood trauma in their history, were offered the service at the time of intake into mental health services. Service users who were receiving treatment in secondary care were excluded from the service, as were those who felt unable to keep themselves safe from acting on suicidal ideation during their wait for treatment, were regularly using substances, or self-harming regularly and/or in ways that were potentially dangerous to their lives.

Service provision

The core intervention used was the attachment-focused (AF-EMDR) protocol (Parnell, 2013; Parnell & Brayne, 2019), along with the provision of psychoeducation and psychological support tailored to individuals’ needs. Sessions were weekly and capped at a maximum of 20 for any one service user. A total of 45 people attended the service over a 36-month period and were treated by one psychologist (the author) experienced in EMDR as well as AF-EMDR, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic psychotherapy. Supervision was initially undertaken once weekly and reduced to fortnightly due to employee turnover and need.

Quantitative and qualitative data were routinely collected to monitor the progress of the clients and of the service. The Structured Interview for PTSD (SI-PTSD) questionnaire was used because it was considered the most appropriate standardised measure available at the time for the purpose intended. While clinicians might prefer to use measures related to complex trauma, decision-makers would be more directly impacted by measures that are in their frame of reference. Given the growing social problem, coupled with the lack of financial provision, and competing needs, the SI-PTSD seemed to be the best tool to address the complex situation. The instrument mirrors all six DSM-IV criteria necessary for a PTSD diagnosis. Data was collected at the start of the first appointment, at the last treatment appointment and at follow-up appointments one month and six months after the completion of treatment. The data were anonymised and matched with an ID number to ensure confidentiality and full anonymity prior to analysis. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software programme was used to analyse the quantitative data.

Additionally, a bespoke qualitative questionnaire was administered at three time points (after the intervention, at 1-month follow-up and 6-month follow-up) to ascertain whether any changes had occurred in the perceptions, behaviours, attitudes and abilities of service users. It enquired about whether after treatment, service users had experienced changes:

(a) in their belief about themselves

(b) as parents

(c) as spouses/partners

(d) in their physical, emotional, and sexual boundaries

(e) in their perspective on their traumatic experiences

(f) about them wanting to change their job in terms of better fulfilling their potential

(g) in their capacity to deal with their emotions

(h) in their ability to honour their own emotions, thoughts, desires, whilst simultaneously respecting those of others

(j) in their ability to accurately assess themselves in these areas.

The qualitative questionnaire was not administered prior to treatment because adults who have experienced childhood trauma, especially relational childhood trauma, are limited in their repertoire and awareness of available emotions (Lemma, 2003). Such individuals are unable to know what they do not know, and an accurate assessment can therefore only reasonably be undertaken once their awareness and range of repertoire of responses grows. What an effective AF-EMDR intervention enables (as this pilot service demonstrates), is an expansion of this repertoire, to include much more of a range of emotions that a person who has not experienced childhood relational trauma would have. The inclusion of item (j) asking them whether they would have been able to accurately assess themselves in these areas prior to treatment or not, was included in the questionnaire to act as a means of verifying whether each of these service users’ experiences matched what the research on this topic so far has recorded.

Results

PTSD symptoms

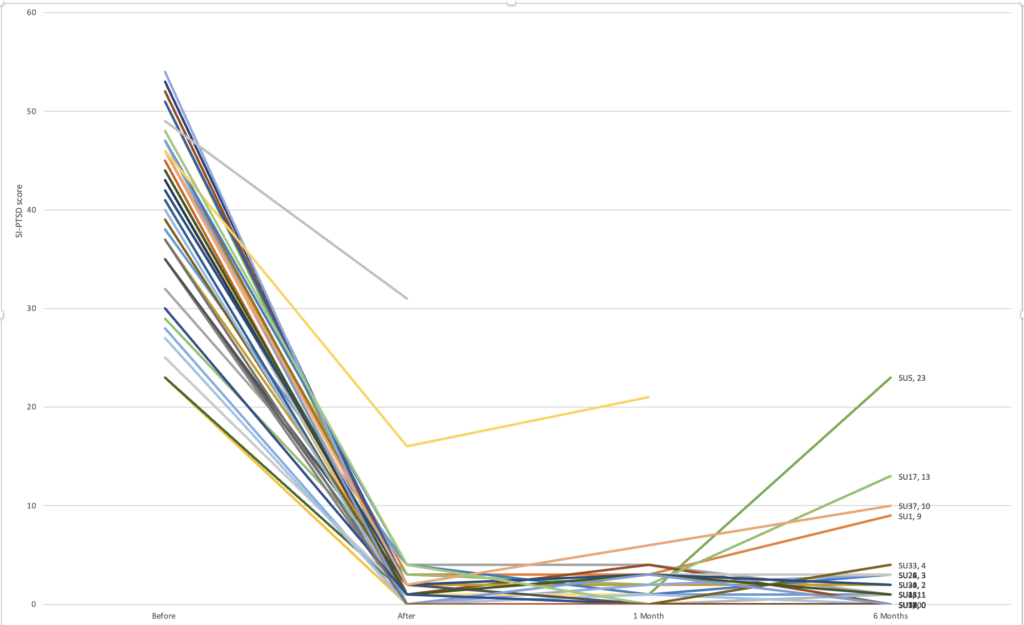

Service users were 45 in total, 11 (24.44%) male and 34 (75.55%) female, ranging in age from 19-73 years old. Nobody dropped out of the intervention phase, but some service-users did not attend their follow-up appointments. The graph below captures the changes in SI-PTSD scores from before treatment to after treatment, and at 1-month and 6-month follow-up.

Except for two service users, there were dramatic improvements in PTSD symptoms post-intervention (scores dropped to between zero to five points on the SI-PTSD scale.)

T-tests were performed to compare symptom reduction of service users pre-intervention (M = 40.41, SD = 8.47) versus post- intervention (M = 1.21, SD = 1.3). Large statistically significant improvements in symptoms were observed t(44) = 28.8, p < .001. These results remained statistically significant at 1-month and 6-month follow-up demonstrating maintenance of improvements after the end of the intervention (Table 1).

| M | SD | t | df | sig | |

| Pre-intervention | 40.41 | 8.5 | |||

| Post-intervention | 1.21 | 1.3 | 28.8 | 44 | p<0.001 |

| 1-month follow-up | 1.76 | 1.57 | 28.37 | 40 | p<0.001 |

| 6-month follow-up | 2.86 | 5.06 | 21.94 | 28 | p<0.001 |

While nobody dropped out during the intervention (n=45), attendance reduced at the follow-up appointments. One client did not attend the 1-month follow-up because they felt they were doing well and did not require further help. Attendance at the 6-month follow-up was lower (n=29). The reasons for not attending were varied but included people who felt they did not need the service, had moved out of the area or who did not respond.

Five service users’ scores at 6-month follow-up increased by more than five points compared to post-intervention. Of these, one person attributed the change to coming off medication. Four reported traumatic experiences post-treatment which were very similar to significant traumatic events they had experienced in their past, causing some degree of symptom recurrence. Three out of these four service users quickly re-stabilised with an additional one to three AF-EMDR appointments, while one was referred to a different service.

Results from the qualitative questionnaire

The data from the qualitative questionnaire was not formally analysed but there were some very obvious trends. Of note is that none of the service users reported a worsening in any area because of the intervention.

| Item | Better (with examples of responses) | Number of clients reporting no change |

| (a) Changes in belief about self | Improved self-worth; self-belief; self-confidence; self-efficacy. Looking forward to living life. | 0 |

| (b) Parenting | More patient with their children; more understanding; calmer; more loving; less detached. | 2 |

| (c) Ability as a spouse/partner | More understanding; more caring; more able to communicate about feelings; able to talk about their pasts; less anxious; less irritable; more able to go out and enjoy life together; more independent; more secure. | 2 |

| (d) Boundaries (emotional, physical, sexual) | In all these areas, those who had been unable to uphold appropriate boundaries of other’s behaviour toward them reported being able to post-intervention, while those who had been unable to honour others’ boundaries reported having a new consciousness of this and implementing appropriate boundaries in their own behaviour towards others. | 4 – emotional boundaries 5 – physical boundaries 13 – sexual boundaries |

| (e) Change in perspective about the traumas experienced | No longer blaming themselves for what had happened; accurate recognition of where the responsibility for the abuse/neglect lay; stronger sense of self-identity; being free of guilt, shame, and despair; better understanding of what happened and why; and no longer being defined by their trauma. | 0 |

| (f) Change job for greater fulfilment | More likely to change job because feeling more confident or empowered and believed they could reach their potential; more positive about their futures and wanted to enjoy what they did, be happy, and productive. | 20 Happy in their current jobs. |

| (g) Ability to deal with emotions | Felt calmer; more relaxed; more rational; able to experience emotions, express them, understand one’s own and others’ emotions better; more in control; not feeling the need to hurt their bodies or act out in order to manage their emotional pain. | 1 |

| (h) Ability to simultaneously respect self and others | Able to hold their own opinions, feelings, and thoughts, whilst simultaneously being able to let others hold theirs without feeling like they were personally wrong or being attacked if their position differed from others. | 9 |

| (j) Ability to self-assess | All reported that prior to the intervention they would not have been able to accurately assess themselves in these areas. | 0 |

Discussion

Service user reports reveal that the benefits of the EMDR intervention extend far beyond just symptom reduction. In light of the aim of this paper to provide perspectives to decision makers that could facilitate their decision making regarding redressing the balance between the provision of care and its burgeoning costs, the two most important findings were: (a) upon receiving appropriate treatment for their needs, service users lives improved dramatically and (b) the outcome was not just the disappearance of PTSD symptoms, but that psychological growth spontaneously occurred as well, resulting in numerous improvements in their personal lives.

The most notable change for service users was how different they felt within themselves. They became calmer (possibly indicating a change in their autonomic nervous system function), and no longer saw themselves through the lens of their neglect and abuse. Instead, they realised their intrinsic worth. The combination of improved autonomic function, awareness of worth and ability to contribute to the world, unlocked self-efficacy and generated confidence. It is the outcomes of these internal changes that caused tangible changes in their behaviours. They spontaneously reported becoming better parents and better adults.

Old dysfunctional ways of interacting changed to constructive interactions, enriching relationships with adults and more importantly, with their children in their foundational years, thereby reducing their exposure to ongoing neglect and ACEs (van der Kolk, 2016). Parents reported responding to their children with greater understanding, compassion, patience, and expressions of love. These are characteristics that aid optimal development of children, setting them up for successful futures; as opposed to the deficits that were resulting from the inability of these caregivers to provide consistent emotional, social, and intellectually enriching environments and role-modelling for their children.

To observe service users report an almost unanimous improvement with adults as well as with their children is of great significance not just to these individuals and their families, but to future generations, and to society. Regulated emotional states support rational thinking in decision making (Siegel, 1999; Porges, 2011; Porges & Furman, 2011) thereby enabling considered (versus impulsive or automatic) behavioural responses to situations, resulting in gains all round.

If this was the effect on adults who were already parents, it might be worthwhile for decision makers to consider how much additional gain may be had from ensuring appropriate service provision to those with traumatic backgrounds who have not yet had children, as it has the potential to forestall dysfunctional brain (and other) development which may have much wider and long-term implications. Maternal mental illness (Hope et al., 2021) and even anxiety, stress and depression during pregnancy can have both short-term as well as long-term effects on children born to these mothers (Lautarescu et al., 2020; Sandman & Davis, 2012; Pearson et al., 2013) even into their adulthood (de Almeida et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2019). Additionally, the recovery from poor child and adolescent mental health is negatively associated with longstanding recovery if one of their parents also suffer from mental health difficulties (Campbell et al., 2021). A retrospective study conducted by Hope et al. (2021) of 489,255 children in the UK concluded that maternal mental illness “costs NHS England £656 million … annually” (p. 515) in accessing child healthcare across all settings. This is not an inconsequential sum. Encouragingly, the reports of positive changes experienced by service users of this pilot study are not unique to this service. Boterhoven et al. (2021) and Wesselmann and Potter (2009) also report similar changes in adults with histories of childhood trauma when their childhood trauma was processed using similar methods.

The universal principle of addressing root causes effectively resulting in the resolution of a multitude of symptoms applies to mental health too and must be considered as a potential approach by decision makers. Initial provision of high quality robust assessment of individuals by highly competent assessors at their entry into mental health services, in tandem with a service offering of the most appropriate treatment with the longest lasting effect, would save considerable distress as well as government finances. If EMDR had equivalence with CBT as a mainstream first-line intervention, this would expand the ability of the NHS to offer the most appropriate treatment for many more conditions in the first instance. Presently, services providing symptom reduction with the shortest number of sessions is the first offer made, by assessors who are often the newest recruits to the primary care service. This approach not only limits effective long term solutions to individuals as early as possible, but it also creates a revolving door syndrome of people repeatedly returning for support for the same symptoms, effectively increasing cost to providers. As populations increase costs will further burgeon unsustainably.

Finally, poor mental health, especially commencing in early life, is associated with diminished ability to take advantage of educational opportunities (Wickersham et al., 2021; Thomas & Morris, 2003; Wittchen et al., 2000), with lower earnings in adult life (Evensen et al., 2017), with lost income and productivity (Latoo et al., 2021; Trautmann, Rehm, & Wittchen, 2016) and unemployment (Wykes et al., 2021; McCrone et al., 2008). This affects economies. A little over half (55%) of service users of this pilot reported that they were more likely to change their jobs, half of whom reported their reasons for this being that they felt more confident or empowered and believed that they could reach their potential post-intervention. To suggest any mental health service as a means of enlarging the financially contributing population would be unethical. It would undermine the integrity of the service offering and perpetuate a lack of trust in the NHS as an institution. However, noting that an improved sense of self was associated to some degree with a greater desire to attain one’s potential through employment must not be ignored either.

Shortcomings and recommendations for future research

Firstly, treatment was offered to service users who were able to manage the emotional effects of confronting their trauma. Individuals with severe psychological or psychiatric difficulties who lack stability may require different treatment approaches.

Secondly, as many service users did not attend their 6-month follow-up, the robustness of the longer-term effectiveness of treatment is not convincingly established. Longer longitudinal studies would contribute to our knowledge of the long-term effectiveness of treatment for childhood trauma, as well as of which factors could hinder longevity of treatment effect.

Thirdly, the number of people who received the intervention was relatively small. So, although the basis for treatment and recommendations made based on the data are sound, larger research studies with control interventions would yield more robust information.

Conclusion

In conclusion, considering mental health support from a broader, longer-term perspective, and providing the longest lasting most effective treatment in the first instance, could result in reduced distress and greater cost-effectiveness, given that psychopathology has at its root, trauma in early attachment. Addressing root causes by strategically supporting population groups who perpetuate childhood trauma could provide significant and long term cost-effectiveness benefits. With this approach, mental health difficulties for the next generation could be forestalled, or at the very least minimised, and ideally prevented. Robust assessments at service users’ entry into the mental health services coupled with a broader range of quality services would aid this pursuit. Finally, providing and rewarding services for accomplishing goals that are better aligned with government vision and assessing cost as well as clinical gains across sectors could facilitate greater co-operation and increased synergy between them.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to honour Frances Sutherland for her commitment to serving the people in her care and David Dobel-Ober for his advice and assistance on statistics and the staff of Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust who made this piece of work possible.

References

American Academy of Paediatrics (2014). Adverse childhood experiences and the lifelong consequences of trauma. American Academy of Paediatrics. https://clark.wa.gov/sites/default/files/fileuploads/public–health/2017/05/acad_peds_impact_of_aces.pdf?msclkid=0ff7226acf5f11ec9fb0e596ce217d 60

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Perkins, C., & Lowey, H. (2014a). National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviours in England. BMC Medicine, 12(72). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741–7015–12–72

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Jones, L., Baban, A., Kachaeva, M., Povilaitis, R., Pudule, I., Qirjako, G., Ulukol, B., Ralevah. M., & Terzici, N. (2014b). Adverse childhood experiences and associations with health-harming behaviours in young adults: Surveys in eight eastern European countries. Bulletin of World Health Organisation, 92(9), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.129247

Bergmann, U. (2020). Neurological foundations for EMDR practice. Second edition. New York: Springer.

Boterhoven de Haan, K. L., Lee, C. W., Correia, H., Menninga, S., Fassbinder, E., Koehne, S., & Arntz, A. (2021). Patient and therapist perspectives on treatment for adults with PTSD from childhood trauma. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(5), 954. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050954

Burke Harris, N. (2014). How childhood trauma affects health across a lifetime. [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/nadine_burke_harris_how_childhood_trauma_affects_health_a cross_a_lifetime?msclkid=6da456ffcf6911ecbf3f5d2062cc31c3

Campbell, T. C., Reupert, A., Sutton, K., Basu, S., Davidson, G., Middeldorp, C. M., Naughton, M., & Maybery, D. (2021). Prevalence of mental illness among parents of children receiving treatment within child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS): A scoping review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(7), 997–1012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787–020–01502–x

CGI Group Inc. (2014). Healthcare challenges and trends. The patient at the heart of care [White Paper]. https://www.cgi.com/sites/default/files/white-papers/cgi-health-challenges-white-paper.pdf

Connected for Life, (2017, June 17). The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. https://www.connectedforlife.co.uk/blog/2017/6/17/the-adverse-childhood-experiences-ace-study

Davenport, T. A., Cheng, V. W. S., Iorfino, F., Hamilton, B., Castaldi, E., Burton, A., Scott, E. M., & Hickie, I. B. (2020). Flip the clinic: A digital health approach to youth mental health service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. JMIR Mental Health, 7(12), e24578. https://doi.org/10.2196/24578

de Almeida, C. Pires., Sa, E., Cunha, F., & Pires, E. (2012). Common mental disorders during pregnancy and baby’s development in the first year of life. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 30(4), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2012.736689

Evensen, M., Lyngstad, T. H., Melkevik, O., Reneflot, A., & Mykletun, A. (2017). Adolescent mental health and earnings inequalities in adulthood: Evidence from the Young-HUNT Study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 71(2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206939206939

Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (1997). The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 9, 2020 from http://www.cdc.gov/ ace/index.htm

Firth, J., Siddiqi, N., Koyanagi, A. I., Siskind, D., Rosenbaum, S., Galletly, C., Allan, S., Caneo, C., Carney, Ro, Carvalho, A. F., Chatterton, M. L., & Stubbs, B. (2019). The Lancet psychiatry commission: A blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(8), 675–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215–0366(19)30132–4

Gregory, A. (2022). Millions in England face ‘second pandemic’ of mental health issues. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/feb/21/england-second-pandemic-mental-health-issues-nhs-covid

Hope, H., Osam, C. S., Kontopantelis, E., Hughes, S., Munford, L., Ashcroft, D. M., Pierce, M., & Abel, K. M. (2021). The healthcare resource impact of maternal illness on children and adolescents: UK retrospective cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 219, 515–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.2216910.1192/bjp.2021.65

Jones, S. L., Dufoix, R., Laplante, D. P., Elgbeili, G., Patel, R., Chakravarty, M. M., King, S. & Preussner, J. C. (2019). Larger amygdala volume mediates the association between prenatal maternal stress and higher levels of externalizing behaviours: Sex specific effects in project ice storm. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 13, 144. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.2216910.3389/fnhum.2019.00144

Karam, E. G., Friedman, M. J., Hill, E. D., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Petukhova, M., Sampson, L., Shahly, V., Angermeyer, M. C., Bromet, E. J., de Girolamo, G., de Graaf, R., Demyttenaere, K., Ferry, F., Florescu, S. E., Haro, J. M., Yanling, M. P. H., Mint, M. H., Karam, … Koenen, K. C. (2014). Cumulative traumas and risk thresholds: 12-month PTSD in the world mental health (WMH) surveys. Depression and Anxiety, 31(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22169

Knapp, M., & Wong, G. (2020). Economics and mental health: The current scenario. World Psychiatry, 19(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20692

Latoo, J., Haddad, P. M., Mistry, M., Wadoo, O., Islam, M. S., Jan, F., Iqbal, Y., Howseman, T., Riley, D., & Alabdulla, M. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic: An opportunity to make mental health a higher public health priority. BJ Psych Open, 7(5), E172. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.1002

Lautarescu, A., Craig, M. C., & Glover, V. (2020). Prenatal stress: Effects on foetal and child brain development. International Review of Neurobiology, 150, 17-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.irn.2019.11.002

Lemma, A. (2003). Introduction to the practice of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley.

McCrone, P., Dhanasiri, S., Patel, A., Knapp, M., & Lawton-Smith, S. (2008). Paying the price: The cost of mental health care in England to 2026. London: Kings’ Fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Paying-the-Price-the-cost-of-mental-health-care-England-2026-McCrone-Dhanasiri-Patel-Knapp-Lawton-Smith-Kings-Fund-May-2008_0.pdf

Office for National Statistics (2020). Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: June 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/

wellbeing/articles/coronavirusanddepressioninadultsgreatbritain/june2020.

Parnell, L. (2013). Attachment-focused EMDR: Healing relational trauma. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Parnell, L. & Brayne, M. (March 2019). Unleash your EMDR. Workshop. In-person. London.

Pearson, R. M., Evans, J., Kounali, D., Lewis G., Heron J., Ramchandani P. G., O’Connor, T. G., & Stein, A. (2013). Maternal depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period: Risks and possible mechanisms for offspring depression at age 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry, 70 (12), 1312–1319. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2163

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological basis of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W., & Furman, S. A. (2011). The early development of the autonomic nervous system provides a neural platform for social behaviour: A polyvagal perspective. Infant and Child Development, 20, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.688

Public Health Wales, (2015). Welsh adverse childhood experiences study. Adverse childhood experiences and their impact on health-harming behaviours in the Welsh adult population. https://phw.nhs.wales/files/aces/aces-and-their-impact-on-health-harming-behaviours-in-the-welsh-adult-population-pdf/

Sandman, C., & Davis, E. (2012). Neurobehavioral risk is associated with gestational exposure to stress hormones: Expert review. Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 7(4), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.1586/eem.12.33

Schore, A. N. (1994). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Schore, A. N. (1996). The experience-dependent maturation of a regulatory system in the orbital prefrontal cortex and the origin of developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 59–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400006970

Schore, A. N. (2001a). Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1–2), 7–66.

Schore, A. N. (2001b). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1–2), 201–269.

Schore, A. N. (2003). Affect dysregulation and disorders of the self. New York: Norton

Schore, A. N. (2009). Relational trauma and the developing right brain: An interface of psychoanalytic self-psychology and neuroscience. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1159, 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749–6632.2009.04474.x

Scott, S., Knapp, M., Henderson, J., & Maughan, B. (2001). Financial cost of social exclusion: Follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. British Medical Journal, 323(7306), 191.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7306.191

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. New York: Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30462-4

Thomas, C. M., & Morris, S. (2003). Cost of depression among adults in England in 2000. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 514–519. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.183.6.514

Trautmann, S., Rehm, J., & Wittchen, H. U. (2016). The economic costs of mental disorders: Do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO Reports, 17(9), 1245– 1249. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201642951

Van der Kolk, B. (2016). Commentary: The devastating effects of ignoring child maltreatment in psychiatry—a commentary on Teicher and Samson 2016. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(3), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12540

Wesselmann, D., & Potter, A. E. (2009). Change in adult attachment status following treatment with EMDR: Three case studies. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 3(3), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933–3196.3.3.178

Wickersham, A., Dickson, H., Jones, R., Pritchard, M., Stewart, R., Ford, T., & Downs, J. (2021). Educational attainment trajectories among children and adolescents with depression, and the role of sociodemographic characteristics: Longitudinal data-linkage study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 218(3), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.160

Wittchen, H. U., Fuetsch, M., Sonntag, H., Muller, N., & Liebowitz, M. (2000). Disability and quality of life in pure and comorbid social phobia. Findings from a controlled study. European Psychiatry, 15(1), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924–9338(00)00211–X

Wykes, T., Bell, A., Carr, S., Coldham, T., Gilbody, S., Hotopf, M., Johnson, S., Kabir, T., Pinfold, V., Sweeney, A., Jones, P. B., & Creswell, C. (2021). Shared goals for mental health research: What, why and when for the 2020s. Journal of Mental Health, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2021.1898552