The different functions of supervision

Do you ever have a moment, when learning about some new idea in therapy, when you wish you could revisit some client from many years before in order to try it out with them? Well, now that I have completed my book on EMDR supervision, the same is happening with me (Logie 2023). “Oh, I could mention that in my book. Too late. It’s with the printers now.” However, if you read this column, you will have access to all my freshest ideas about EMDR supervision!

Whereas my book is aimed at the reader who is an EMDR consultant or those who are training to become consultants, this column aims to be relevant to every EMDR therapist as we are all (hopefully) in receipt of supervision and need to be aware of the process of supervision and how it may assist us.

In this issue I want to look at the different functions of supervision. What is supervision for? As long ago as 1988, terms ’formative’, ’restorative’ and ‘normative’ were coined by Proctor (1988) and these terms will be familiar to many readers to describe the three principal functions of supervision. Other terms have been used by different writers on supervision but none of these have felt satisfactory to me, particularly in relation to EMDR supervision. Eventually I came up with the terms ’educating’, ’enabling’ and “evaluating” in order to describe the three main functions. (Actually, the first of these I initially called ’teaching’ but a wise trainee on my consultant’s training last year pointed out that educating is a more global word than teaching and also means that all three can start with the letter ’E’ so that I can now call them ’the three Es’!) I will leave it to you to guess which of Proctor’s original terms these refer to.

Educating

This is an obvious starting point when looking at the functions of EMDR supervision. The role of my supervisor is to educate me about EMDR and its standard protocol by hearing about my cases, especially where things have got stuck; as well as by observing my EMDR therapy on video recordings or in vivo. It is inevitable that, even if I have attended the best basic training and been attentive throughout, I will have not grasped everything that was presented. It is in the very nature of normal adaptive information processing that we need time to assimilate what we are learning with what we already understand. So, during my EMDR training, I may have missed the next part of the presentation, whilst I was mentally digesting some particular nugget of information that had just been imparted. Thus, trainees will end the training with gaps in their understanding of EMDR. It is my supervisor’s job to spot and help me to plug these gaps.

Enabling

Enabling is about encouragement and support. For therapists who are new to EMDR, for example, it is common for there to be some reluctance to start the actual processing phase of therapy. For one of my supervisees this became a real sticking point and a recurrent theme in supervision, until she decided to have some EMDR herself on this issue with another colleague. Sometimes what I need as a supervisee is not teaching but something to boost my confidence. Perhaps all that is required from my supervisor is, “that’s great! Yeah, just crack on!” Sometimes, when the supervisee seems really stuck, I will ask the flashforward (Logie & De Jongh, 2014) question: “what’s the worst thing that could happen if you started processing now?” But sometimes the enabling function is more in relation to ’sharing the awfulness’. For example, I might say to my supervisor, “I’m not stuck with this client, but I have just had a really upsetting session with them and I feel that I need to share it.”

Evaluating

The supervisor’s role is also to evaluate my practice, particularly in relation to the process of accreditation. There may be times during supervision when this is occurring in quite a formal way such as when my supervisor is viewing my videos. But it is also likely to happen throughout the supervision process as my supervisor is gauging how well I am understanding case conceptualisation or how well I understand the standard protocol.

In a later column I will examine each of these functions in more detail. But for now I will continue with some other ideas that I have found useful in finding a theoretical basis for understanding EMDR supervision. Another story is helpful to introduce this.

The seven-eyed model of supervision

This story is about my own experience of being a supervisee many years ago, before I was involved with EMDR. I had a supervisor named Michael who is German and with whom I had an excellent supervisory relationship. I had an adolescent client, probably autistic, who repeatedly expressed neo-Nazi opinions during his sessions with me, making comments such as “six million Jews wasn’t enough”. As the son of a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany myself, I was understandably very distressed by this and decided to take it to supervision although this was with some trepidation as I was aware that this might be difficult for Michael considering his own background. In supervision I started by explaining the context of my distress by disclosing my own heritage which I had not previously done. Before we actually discussed my case, Michael shared that his wife was also from a second-generation German Jewish refugee family. He was very supportive and helpful in discussing this particular case. In fact, my wife and I later became friends with them both.

This story illustrates how what is happening with the client can have resonances for the therapist which, in turn, may affect the therapist/client relationship. When brought to supervision, the therapist’s ’stuff’ may resonate with what is happening for the supervisor and bring up their own stuff which may, in turn, affect the supervisory relationship.

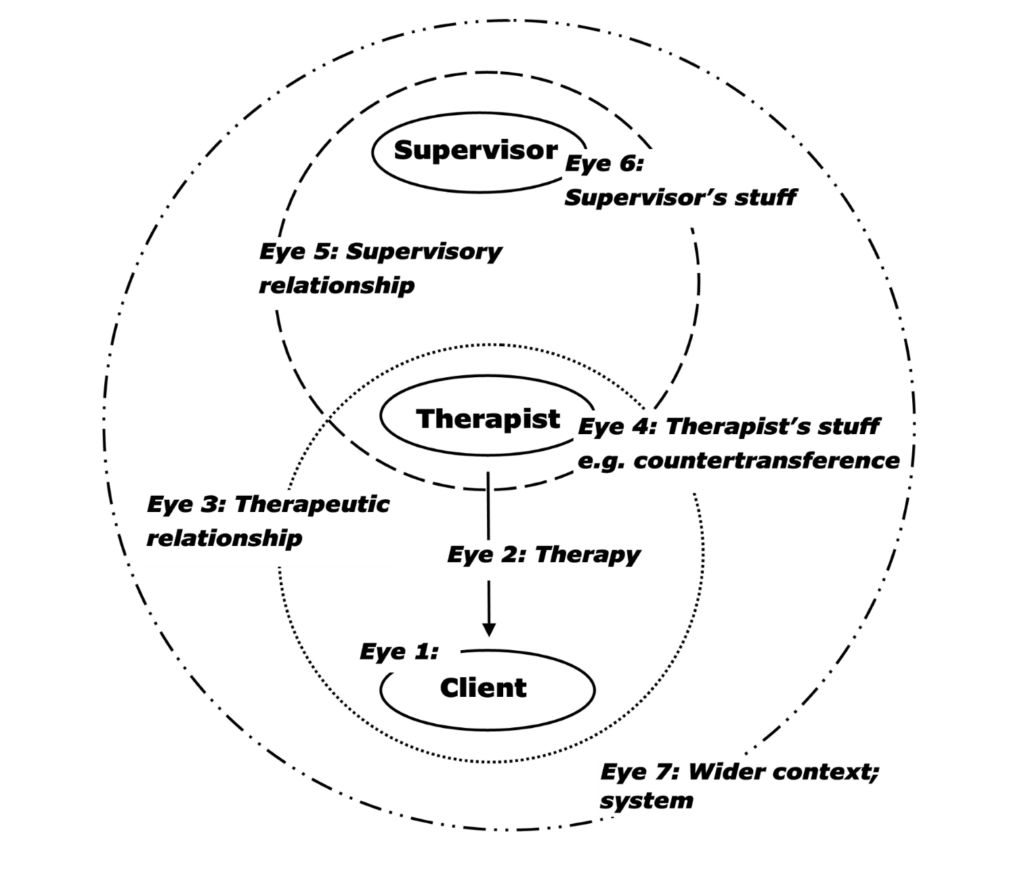

The easiest way to describe this model is in diagrammatic form as follows in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The seven-eyed model of supervision (Hawkins, 1985; Hawkins & McMahon, 2020)

According to the seven-eyed model of supervision of Hawkins and Shohet (Hawkins, 1985; Hawkins & McMahon, 2020) the supervision process is seen through the lens of seven different ’eyes’, based upon the three people to whom supervision relates:

- Supervisor

- Therapist (supervisee)

- Client

I will describe each of the seven ’eyes’ and how this may be relevant, in particular, to me as an EMDR therapist.

Eye one: The client

Often, what is occurring during a supervision session is that I am describing my client, for example, their presenting problems, history, personal resources or demeanour during the session.

Eye two: The therapy

Here, I will be telling my supervisor what therapy I am providing, or the intervention I am contemplating. The focus is on ’what to do’ i.e., the therapeutic intervention.

Eye three: The therapeutic relationship

With this eye, the focus is not on the client or the therapy, but on the relationship between me and my client. At times, I may be having problems in therapy, not because I don’t understand the client (Eye one) and not because I don’t know an effective way of helping them (Eye two) but because the therapeutic relationship is not conducive to therapeutic change. This may be due to lack of trust. It may be due to transference. The client may not want to ’get better’ because they might risk losing the relationship they have with me.

Eye four: The therapist’s ’stuff’

It may be that my own issues or unprocessed adverse life events are getting in the way of the therapy progressing. For example, the client reminds me of my own mother or my client’s experience of bereavement awakens unprocessed grief in me. At times, supervision may need to address my difficulties which are triggered by what is happening in the therapy session. In EMDR therapy, we talk about the ’blocking beliefs’ held by the client which may impede processing in a therapy session. Similarly, I may hold a blocking belief of my own which may prevent me from responding or acting in a way that is therapeutic for my client.

Eye five: The supervisory relationship

Here the focus is on the relationship between me and my supervisor. There may exist tension between us which bears no relation to the client in question. For example, I may be eager to be approved for accreditation by my supervisor and therefore fail to disclose my own doubts and mistakes in order to create a good impression.

However, the client under discussion might also affect what is happening in supervision. A ’parallel process’ (Doehrman, 1976; McNeill & Worthen, 1989) may be occurring in which the supervisory relationship is manifesting similar relationship dynamics to those in the therapeutic relationship. For example, a particular client may be very dependent on me which may be reflected in me feeling unusually dependent on my supervisor when discussing this particular client. Or a client whose negative cognition (NC) is “I’m not good enough” may manifest in the parallel process as me feeling “I’m not a good enough therapist”. What happens in the therapy room may be re-enacted in supervision and, conversely, what happens in supervision may be re-enacted in the therapy room.

Eye six: The supervisor’s ’stuff’

It may be that the supervisor’s own unprocessed past experiences are getting in the way of them being able to effectively assist the therapist. This may be in the form of countertransference where I remind my supervisor of someone from the past with whom they had a difficult relationship that was never resolved.

However, it can also be useful for the supervisor to use their own emotional reactions as a barometer to ascertain what is occurring in the therapy room.

Eye seven: The system

Therapy always occurs in a context. For example, who is funding the therapy and what influence do they have about how it proceeds? If the therapy is on the NHS, is there a limit to the number of sessions or a limit on what events can be targeted during processing? If it is funded by a compensation claim, must the processing only be in relation to the accident in question? And if a relative is paying for the therapy, what is their attitude to the therapy and how it should be conducted? In this situation the supervision is not relating to three people (client, therapist and supervisor) but to four or more.

Bringing it together

As you will probably have realised by now, I like to teach by telling stories. One of my supervisees once said, “I love hearing your stories, Robin, especially the ones about when you got things wrong!” So here is another story to finish with about something that happened only a couple of months ago. A supervisee, who I have worked with for many years, was presenting a case to me. The first thing she told me about her client was that he was very controlled and she felt that she needed to be quite controlling to keep him safe until they had resources safely in place. She described it as a “rather constipated” start to the therapy.

Quite instinctively I started to fire lots of questions at her and, uncharacteristically, I felt I was interacting in a controlling, macho way which meant she was unable to really share with me what her dilemma was in relation to this client. After a few minutes I stopped in my tracks and said, “that’s weird. What’s going on? It looks like some parallel process is happening.” My supervisee replied, “it certainly does!” and we were able to laugh about it together. I did not really understand what had just occurred and, because I was writing about it for this column, I got in touch with her for her perception of what had happened. This is what she said:

“Supervision echoed this beautifully in the parallel process. You firmly held me back from telling you the trauma, like you were trying to control the flow of information from me, exactly as I did from him. It didn’t feel macho, but it felt constrained. In terms of whether it helped – it was a curious and fascinating process in supervision, but not unpleasant. It was very helpful for me to reflect on my own behaviour and my silent anxiety about re-traumatising my patient, and I think it helped me to ease up and trust him – that he was ready to talk – and to not ‘over-fragilise’ him, to use a Marsha Linehan term. It gave me a sense of how I had been with him. The patient’s reflection was that he felt cared for, safe and contained. And I would echo this in supervision. But interestingly, by this point in supervision, I was ready to talk, and on reflection, I think my patient was too. But we were all three of us a little nervous as to whether we could each handle what was about to come.”

Hopefully this story shows how the seven-eyed model can help us understand what is happening in supervision and how best we can make use of the supervisory relationship. It also illustrates how, just as in EMDR therapy we sometimes have to trust the process without really understanding what is happening for our client, the same can occur in supervision.

References

Doehrman, M. J. G. (1976). Parallel processes in supervision and psychotherapy. Bulletin of the Meninger Clinic, 40, 9-104.

Hawkins, P. (1985). Humanistic psychotherapy supervision: A conceptual framework. Self & Society, 13(2), 69-76.

Hawkins, P., & McMahon, A. (2020). Supervision in the helping professions (5th ed.). London: Open University Press.

Logie, R. (2023) EMDR supervision: A handbook. Routledge.

Logie, R., & De Jongh, A. (2014). The “Flashforward procedure”: Confronting the catastrophe. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 8(1), 25-32.

McNeill, B. W., & Worthen, V. (1989). The parallel process in psychotherapy supervision. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 20(5), 329.

Proctor, B. (1988). Supervision: A co-operative exercise in accountability. In M. Marken & M. Payne (Eds.), Enabling and ensuring. Leicester: National Youth Bureau and Council for Education and Training in Youth and Community Work.