Neuro EMDR: Applying EMDR therapy with clients who have impaired cognitive abilities

EMDR therapy has been shown to be highly effective and time efficient in addressing trauma memories in both adults and children. However, there are questions about how EMDR can be effective with adults who have experienced a brain injury or are experiencing other cognitive difficulties. This article summarises some of the recent research within the area and proposes adaptations to the standard protocol that can be made to make best use of EMDR therapy in this population.

Introduction

Within the UK in 2019-2020 there were 356,669 UK admissions to hospital with acquired brain injury (ABI), or any brain injury that has occurred after birth including traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke or brain tumours, which is a 12% increase since 2005-2006 (Headway, 2023). In 2019, there were approximately 977 TBI admissions per day to UK hospitals, one every 90 seconds. The diagnostic criteria for TBI on the DSM V states that there must be an “impact to the head or other mechanisms of rapid movement or displacement of the brain within the skull with one or more of the following: loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia, disorientation and confusion, neurological signs such as neuroimaging demonstrating injury or a worsening of a pre-existing seizure disorder” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnostic criteria also consider the severity ratings for TBI which are outlined in the table below.

| Injury characteristic | Mild TBI | Moderate TBI | Severe TBI |

| Loss of consciousness | Less than 30 minutes | 30 minutes – 24 hours | Greater than 24 hours |

| Posttraumatic amnesia | Less than 24 hours | 24 hours – 7 days | Greater than 7 days |

| Glasgow Coma Scale on assessment | 13-15 (not below 13 at 30 minutes) | 9 – 12 | 3 – 8 |

The diagnostic criteria for mild TBI have recently been reviewed and updated by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine to include a range of external forces that cause TBI. This includes the head being struck with an object (which can include intimate partner violence), head striking a hard object or surface, the brain experiencing acceleration/deceleration movements such as in road traffic collisions (RTC) and forces generated from a blast or explosion (Silverberg & Iverson, 2023). When we consider these causes, it is possible that we may be seeing many more people with TBI than we realise in our routine clinical practice.

Research has suggested that in the general population the prevalence rates for brain injury are between 8% to 12% (Frost et al., 2013; Silver et al., 2001). Williams et al. (2010) found that up to 60% of adult male prisoners had experienced a head injury, with around 15% experiencing a moderate to severe TBI. McMillan et al. (2021) found that across four prisons, 78% of women prisoners had experienced a significant head injury and 40% of these women had associated disability. Of those women who had experienced a significant head injury, 84% of them had experienced repeated injuries and 89% of these repeated injuries were because of domestic violence.

Kent & Williams (2021) completed research with male young offenders between the ages of 16-18 and found that 74% reported a TBI of any severity within their lifetime and 46% had experienced a head injury leading to a loss of consciousness. Furthermore, research on adolescents in young offenders’ institutions who have experienced a TBI are more likely to experience mental health problems including self-harm and suicide (Chitsabesan et al., 2015).

Bryant (2011) suggested that people who experience TBI can also develop PTSD. Quershi and colleagues (2019) completed a cross sectional study on 171 individuals who attended a TBI clinic over an 18-month period. Participants were asked to complete the PTSD Checklist Civilian Version (PCL-C) along with other psychometrics. The results from the study showed that PTSD was 21% more prevalent in this population and that there was a clear link between TBI and PTSD within the civilian population in the UK (Quershi et al., 2019).

Based on this research it could be argued that mild TBI may be a more prevalent issue in the clients who routinely present for EMDR therapy with practitioners. For example, we may often see clients who have experienced significant trauma because of domestic violence that may involve impact trauma to the head and brain. Therefore, it is appropriate to consider how we can adapt EMDR to meet the needs of people who have experienced a TBI.

The current evidence base for applying EMDR to clients who have a TBI

There are several articles and case studies that highlight that EMDR can be effective in individuals who have experienced a mild TBI and have PTSD. In one conference presentation a single case study of adapting EMDR to a client who had TBI and difficulties with aphasia, or speech, was presented (Gene-Cos, 2010). The presenter highlighted how each person with TBI is unique and therefore adaptations need to be made to suit the individual. In a further case series EMDR was used to address the emotional and behavioural aspects of mild TBI in three clients (Jayatunge, 2013).

In a single case study of a 17-year-old young man who experienced significant facial injuries and a brain injury following an explosion, EMDR was used as part of his rehabilitation to address the consequent PTSD (Fritzche, Hyckel, & Ziegenthaler , 2013). EMDR was effective at reducing PTSD symptoms and significantly helped with the individual’s rehabilitation. The authors argue that EMDR used early on after a TBI can have significant positive effects. A conference presentation by Gibson (2015) highlighted how EMDR could be adapted to a client with TBI and the importance of offering EMDR to this client group due to the association between TBI and PTSD (Gibson, 2015).

One case study observed the effectiveness of EMDR in addressing persistent post-concussion symptoms (PCS), depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (Moore, 2021). A 57-year-old man who sustained a mild TBI from a serious RTC and developed PCS, had nine 90-minute EMDR sessions across a five-month period. The client was assessed at pre, mid and final treatment as well as at an 18 month and 5-year review. The measures used to assess the client included the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 item version, (Kroenke et al., 2001), the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 item questionnaire (Spitzer et al., 2006), The Impact of Events Scale Revised (Weiss & Marmar, 1997), and the Rivermead Post Concussion Questionnaire (King, 1997). Further measures were taken including the Phobia Scale (National Health Service, 2011) and the Work and Social Adjustment Scales (WSAS; Mundt et al., 2002). In addition, Moore (2021) used subjective units of distress (SUD) related to the specific trauma memory he treated with EMDR as well as the validity of cognition (VoC) score for how much the client believed the positive cognition related to the trauma memory to be completely true. The results showed that following EMDR there was a significant reduction in all PTSD, depression, anxiety and PCS symptoms that were sustained at both 18 months and 5 years follow-up (Moore, 2021).

A more recent case study highlighted how more intensive EMDR successfully treated PTSD in a client who had experienced TBI (Yasar et al., 2022). The researchers completed a 16 month follow-up and the PTSD symptoms were maintained at a significantly reduced level. A further single-case study completed by Moore (2023) used EMDR to address post traumatic distress related to post traumatic amnesia (PTA) following a severe TBI. The results of the case study, using outcome measures, pre and post eight sessions of EMDR therapy and at 4 year follow-up, such as the Impact of Events Scale (Wiess & Marmar, 1997), SUD and VoC, demonstrated significant success at reducing PTSD symptoms to a sub-clinical level as well as sustained low SUD and high VoC at 4 years follow-up.

A neuro EMDR perspective

A central aspect to EMDR is the adaptive information processing model (AIP) which is described as the brain’s ability to process information adaptively so that humans can survive, heal, integrate and adapt to their environments and experiences (Shapiro, 2018). When taking a neuropsychological perspective to understanding TBI we often focus on three aspects when formulating the client’s difficulties:

- The individual’s diagnosis based on CT or MRI scan of location of brain injury

- The direct observations of family members or multidisciplinary team (MDT) members

- The results of cognitive assessments (Wilson & Betteridge, 2019).

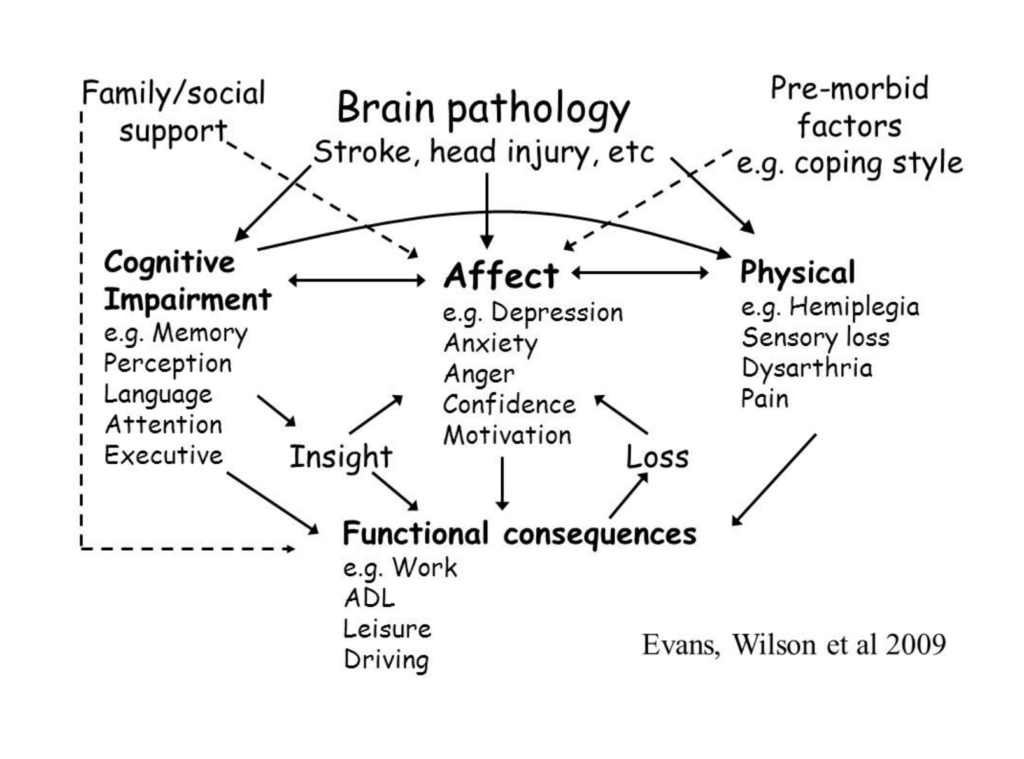

This information is then considered in a neuropsychological formulation which is outlined in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Neuropsychological formulation

The formulation model shown in figure 1 is a key tool for neuropsychologists to use when working with a client who has experienced a TBI. The model focuses on the impact of the TBI on an individual’s cognition, such as on their memory or attention, their affect, such as possible depression or anxiety following the TBI, as well as the physical impact of the TBI (Wilson et al., 2009). In addition, the model highlights the importance of an individual’s pre-existing coping style or possible cognitive reserve, meaning the person’s level of cognitive functioning prior to the TBI (Wilson et al., 2009). Furthermore, the model also highlights the importance of family and social support on affect as well as the importance of an individual’s level of insight into their difficulties, experience of loss and the functional consequences of the TBI (Wilson et al., 2009). It could be argued that, based on this formulation model, EMDR could have a strong role to address a range of these factors such as the individuals experience of loss, possible depression or anxiety and to provide support to the family who may be traumatised by the impact of the TBI on their loved one.

Considering these factors, and based on the authors’ experience of neuropsychology and working with brain injured clients, the following key domains of cognition can be considered:

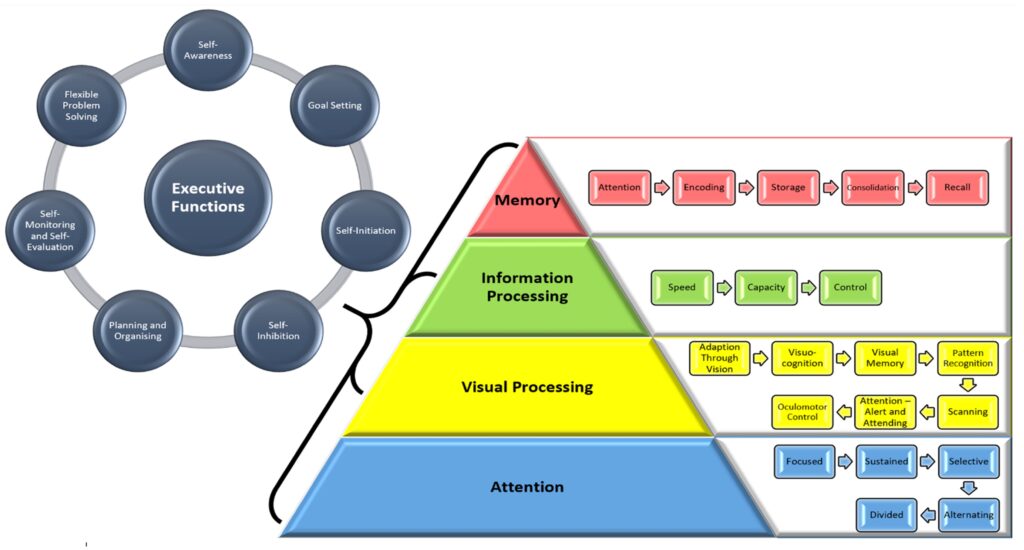

Figure 2. Domains of cognition

The above figure, drawn from a broad range of cognitive models and concepts in cognitive rehabilitation therapy (Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977; Warren, 1993; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974; Diamant & Hakkart, 1989; Brannagan & Malia, 2005), has been used by the author to help consider each individual’s cognitive functioning and domain specific aspects of different cognitive functions. These include attention, visual processing, information processing, executive functions and memory. Whilst these are framed as separate aspects the reality is that all of these cognitive functions are often occurring simultaneously when an individual is in EMDR therapy. These cognitive domains are considered below and cognitive rehabilitation strategies for individuals with difficulties in each domain are proposed in relation to how EMDR can be applied.

Adaptive information processing

EMDR relies on an individual’s ability to hold both a traumatic memory in mind alongside focusing on dual attention stimulus (DAS) such as eye movements, tactile sensors or auditory stimulation (Shapiro, 2018). Therefore, we need to consider an individual’s ability to select, sustain and divide their attention for periods of up to 30-40 seconds, depending on the material that is coming up in the processing. In addition, we also need to consider an individual’s capacity, control and speed of information processing. From a neuropsychological perspective, we would assess this on direct observation, such as seeing if someone can sustain their attention on questions that have been asked of them and if they are able to stay on topic within an assessment session. We may also consider the results of neuropsychological assessments, as attention and information processing underpin an individual’s memory.

Using cognitive rehabilitation strategies across the 8-phase standard EMDR protocol

There are some general cognitive rehabilitation strategies that we would recommend to clients who have experienced a TBI as well as their respective family members or staff working with them. Based on the authors’ experience, of using EMDR with this client group we describe these strategies and show how they can aid in our work (see Table 2).

| EMDR Phase | Cognitive rehabilitation strategies |

| 1. History taking | i. Reduce distractions in the client’s environment and slow down your rate of speech. Use more verbal prompts to bring the client back onto task by gently repeating the same question if necessary. ii. Write down with the client different targets that they report in their trauma history. It is more likely you will be able to pinpoint memories prior to the event that caused the TBI and that they may not be able to recall the accident/incident itself but consider enquiring about when they first woke up or when they first realised the impact of the TBI/injuries they sustained. iii. Consider pacing the sessions depending on how much fatigue or pain the client is experiencing. iv. If the client has significant memory problems, in terms of encoding new information to memory, then consider re-introducing yourself in each session and highlight that they may not recall but that you have discussed with them about EMDR and past trauma memories that you have both written down and check back with them if they are okay to proceed. v. An additional strategy can be, with the client’s permission, to record a video or audio clip of yourself explaining EMDR and the date of the next session so that they can be prompted either by family or care staff to review it before the next session. |

| 2. Stabilisation | i. Write down or use other memory strategies such as voice dictation on the client’s mobile phone, with their consent, strategies such as grounding, the use of an imaginary container for their trauma memories as well as their safe space. ii. With the client’s permission set reminders on their mobile phone at suitable times of day for them to be prompted to practice these new skills. iii. Have the skills written down in front of the client when planning to do EMDR processing so that they are easily accessible and can be followed rather than relying on their memory. iv. Consider using more external cues such as pictures, music or smells/tactile materials over asking the client to picture a safe space in their mind as this may be less cognitively demanding. |

| 3. Assessment | i. When asking the assessment phase standard protocol questions stick to the shortness of the protocol and consider repeating back a summary of what the target memory is, for example, rather than using the words incident or image – for example, “when you bring up that incident of when you first woke up after the accident and realised you could not walk what words best describe a negative belief about yourself now?”. By being explicit about the target image each time it serves to aid sustained attention and also with errorless learning, that is giving the client the correct information first time to ensure that they are more likely to encode it to memory (Betteridge, Wilson, 2019). ii. Be prepared to repeat the questions from the assessment phase multiple times if the client is easily distracted. iii. When eliciting the negative and positive cognition from the client initially use the standard protocol questions and approach but if this is too abstract or difficult for the client, consider the context of the trauma memory and offer cognitions in different domains for example “when you bring up that incident of when you woke up after the accident and realised you could not walk, what negative belief do you have about yourself now? Would it be I am powerless? I am weak? Or I am unsafe?” iv. Consider using written aids of cognitions for the client to choose from if they cannot generate their own as this may be too difficult for their executive functions, depending on the type and nature of brain injury. v. If the client is still stuck with identifying suitable negative and/or positive cognitions after the above strategies, consider proposing “I am powerless” for the negative cognition and “I am more okay now” for the positive cognition as these cognitions may possibly suit most traumatic experiences that clients face. |

| 4. Desenstisation | i. Eye movements may be difficult for TBI clients who have visual spatial difficulties and have either neglect on one side of their brain or poor oculomotor control. Therefore, we would advocate for the use of tapping / tactile sensors if clients have sensation in both hands. If not, then we would suggest using auditory BLS. ii. Consider shorter sets of BLS depending on the clients’ levels of fatigue. iii. If the client becomes easily distracted, consider going back to the target image and be more explicit about the image/incident to cue them back into the memory that you are focused on. v. There is a chance that the memory may reprocess quickly, similar to how trauma reprocessing can work in children. |

| 5. Installation of positive cognition | i. In built into the standard protocol is the re-evaluation of the original positive cognition that the client stated in the assessment phase which is useful as a memory prompt and to regain the client’s attention on processing. ii. Like the assessment phase the client may need additional prompting to pinpoint a suitable positive cognition that they feel is completely true. This may include the need for the therapist, based on the material that has been re-processed in the desensitisation phase, to put forward different cognitions in different domains or, if this is too difficult for the client, to propose a positive cognition of “I am more okay now” or “I am safer now.” |

| 6. Bodyscan 7. Closure | i. Some clients may have either numbness or increased sensitivity in their body as a result of the brain injury therefore we would recommend being patient and working with what the client presents with here, and that some of the sensations presented in the body scan could be unrelated to the original trauma memory, such as pain. ii. When closing a session consider using additional memory aids, such as pictures, music or smells for the safe space that you used in the stabilisation phase. |

| 8. Re-evaluation | i. Depending on the client there is a possibility that they may not recall the previous EMDR session and therefore they may need more explicit prompting regarding the trauma memory that has been worked on, such as by saying to the client “you may not recall but we did some EMDR work on a previous difficult trauma memory in our last session of when you first realised you could not walk, if you focus on that memory what do you get now?” |

Summary and conclusions

This article has focused on the evidence base, neuropsychological theories and practical cognitive rehabilitation strategies of how to apply EMDR to clients who have experienced a TBI. Within the authors’ experience EMDR has been very useful in addressing the PTSD aspect of TBI and aided client’s engagement in neuro rehab. Whilst the article’s focus has been on TBI, the strategies presented, we would argue, may be useful for a broad range of presentations such as for people with learning disabilities, clients who have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as well as clients who have functional neurological disorders. Further larger-scale research is needed to consider the applicability to the TBI client group.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Baddeley, A. D. & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. Psychology of learning and motivation, Volume 8, pp 47-89.

Brannagan, K., Malia, K. (2005). How to do cognitive rehabilitation therapy: A guide for all of us. Lash & Associates Publishing Inc.

Bryant, R. A. (2011). The cutting edge: Mental disorders and traumatic brain injury. Depression and Anxiety, 28, pp: 99-102.

Chitsabesan, P., Lennox, C., Williams, H., Tariq, O., Shaw, J. (2015). Traumatic brain injury in juvenile offenders: findings from the comprehensive health assessment tool study and the development of a specialist linkworker service. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, Mar-Apr, 30(2), pp: 106-15.

Diamant, J. J., & Hakkaart, P. J. W. (1989). Cognitive reghabilitation in an information-processing perspective. Cognitive Rehabilitation, 22-29.

Fritzsche, U., Hyckel, A., & Ziegenthaler, H. (2013). [Trauma psychotherapy under use of EMDR as part of the brand-injured rehabilitation illustrated by a case-documentation]. Jahrestagung der Deutschsprachigen Arbeitsgemeinschaft fr Verbrennungsbehandlung (DAV 2013). Mayrhofen, sterreich. German

Frost, B. R., Farrer, T. J., Primosch, M., & Dawson, W, H. (2012). Prevalence of traumatic brain injury in the general adult population: A meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology, 40 (3), pp 154-159.

Gene-Cos, N. (2010, April). New ways of working with complex PTSD and head injury. Presented at the 2nd Bi-Annual International European Society for Trauma and Dissociation Conference, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Gibson, M. (2015, April). EMDR and traumatic brain injury: A case analysis. Presented at the EMDR Canada Annual Conference, Vancouver, BC.

Headway, (2023). https://www.headway.org.uk/about-brain-injury/further-information/statistics/

Jayatunge, R. M. (2013, December). Treating mild traumatic brain injury with EMDR. LankaWeb. Retrieved from http://www.lankaweb.com/news/items/2013/12/18/treating-mild-traumatic-brain-injury-with-emdr/ on 12/18/2013.

Kent, H., Williams, H. (2021). Traumatic brain injury, Academic insights, HM Inspectorate of Probation. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Probation

King, N. S. (1997). Mild head injury: Neuropathology, sequelae, measurement and recovery. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 161–184. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01405.x

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ9. Journal of General International Medicine, 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Lagarde, E., Salmi, L., Holm, L. W., & Contrand, B., (2014). An association of symptoms following mild traumatic brain injury with posttraumatic stress disorder vs postconcussion syndrome. Journal of the American Psychiatry Association, 71(9), 1032-1040. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.666

McMillan, T., Aslam, H., Crowe, E., Seddon, E., & Barry, S. J. E. (2021). Associations between significant head injury and persisting disability and violent crime in women in prison in Scotland, UK; A cross-sectional study. The Lancet Psychiatry, Vol 8 (6), pp: 512-520.

Moore, P. S. (2021). EMDR treatment for persistent post-concussion symptoms following mild traumatic brain injury: A case study. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 15(4), 157-164. doi:10.1891/EMDR-D-21-00015

Moore, P. S. (2023). Treating distressing islands of memory: severe TBI and EMDR treatment for distressing experiences during post traumatic amnesia. Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil 2023;22(1):8-10 https://doi.org/10.47795/UTTR3399

Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. M. (2002). The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 461-464.

National Health Service. (2011). The Improving access to psychological therapies data handbook vs2. National Health Service.

Quershi, K. L., Upthegrove, R., Toman, E., Sawlani, V., Davies, D, J., & Belli, A. (2019). Post-traumatic stress disorder in UK civilians with traumatic brain injury: An observational study of TBI clinic attendees to estimate PTSD prevalence and its relationship with radiological markers of brain injury severity. BMJ Open, Vol 9 (2).

Schneider, W. &and Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review, 84, 1-66.

Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Basic principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.) New York: Guilford Press.

Silver, J. M., Kramer, R., Greenwald, S., & Wiessman, M. (2001). The association between head injuries and psychiatric disorders: Findings from the New Haven NIMH epidemiologic catchment area study. Brain Injury, November, 15 (11), pp: 935-45.

Silverberg, N. D. & Iverson, G. L. (2023). The American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine diagnostic criteria for mild traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2023.03.036

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Lowe, B. (2006). Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD-7). Archives of International Medicine, 166, 1092–1097. https://doi. org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Warren, M. (1993). A hierarchical model for evaluation and treatment of visual perceptual dysfunction in adult acquired brain injury, Part 2. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Jan 47(1), pp 55-66.

Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The impact of event scale revised. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD (pp. 399–411). New York: Guilford.

Williams, H. W., Cordan, G., Mewse, A. J., & Tonks, J. (2010). Self-reported traumatic brain injury in male young offenders: A risk factor for re-offending, poor mental health and violence? Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(6), pp: 801-812.

Wilson, B. A., & Betteridge, S. (2019). Essentials of neuropsychological rehabilitation. New York: The Guilford Press.

Wilson, B. A., Gracey, F., Evans, J. J., & Bateman, A. (2009). Neuropsychological rehabilitation: Theories, models, therapy and outcome. Cambridge University Press.

Yaşar, A. B., Altunbas, F. D., Picard, I. T., Gündüz, A., Konuk, E., & Kavakci, Ö. (2022). Traumatic brain injury (TBI) and concentrated EMDR: A case study. Turkish Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 25, 123-129. doi:10.5505/kpd.2022.13911