Is EMDR Therapy in danger of splitting?

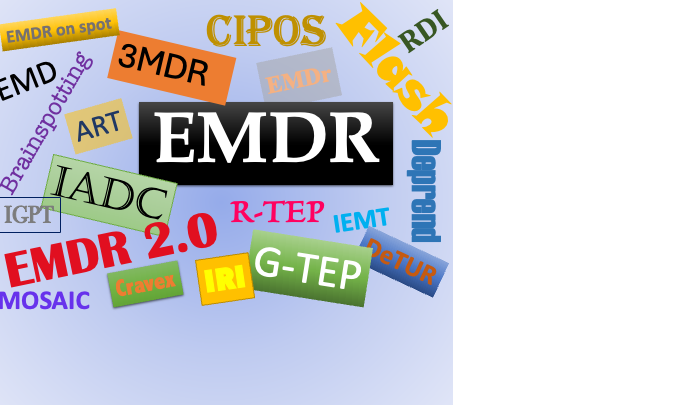

It’s 32 years since since Francine Shapiro published her ground-breaking paper describing EMD (Shapiro 1989); two years later she changed the name to EMDR to describe the reprocessing that practitioners of the new approach were continually witnessing in their work with clients (Shapiro 1991). Since that time, EMDR has emerged as a comprehensive psychotherapy and its adoption is growing fast worldwide. At this year’s European Conference on ‘Challenges of the decade’ Peter Liebermann took the opportunity to focus his keynote address – Between riding on principles and whateverism – where is EMDR going? – on the plethora of techniques, approaches, developments and, inevitably, acronyms that have emerged since Shapiro’s 1989 paper and the opportunities and threats they have brought with them. As one colleague put it after hearing his presentation, “it made me wonder whether EMDR wasn’t itself experiencing ‘structural dissociation’”.

The gist of Liebermann’s presentation was to describe the dilemma we face when, in encouraging and welcoming development of the therapy, we risk drifting so far from Shapiro’s vision that we dilute and degrade it and thereby jeopardise EMDR’s reputation and proven record of efficacy. So, what might grasping the horns of this particular dilemma look like?

Do we need several volumes of scripted protocols?

Liebermann didn’t pull his punches. When we notice that EMDR isn’t working that well, he said, we sometimes find it necessary to adapt. “But do the changes make sense”, he asked. “Maybe some of you may be offended by what I’m saying… and that is on purpose”. Liebermann spoke plainly and raised several areas of concern. He used Michael Hase’s (2021) conceptualisation the ‘structure’ of EMDR therapy comprising six levels and took each in turn, asking:

- Do we need to add to the AIP model by incorporating the structural dissociation model and the idea of pathogenic memories?

- Do we need such detailed and numerous cultural adaptations?

- Do we need several volumes of scripted protocols?

- Do we need to spend so much time and effort seeking the holy grail of a mechanism for EMDR (after all, which psychotherapy can really explain how it works?)

Liebermann began by admitting that his presentation may end up raising more questions than providing answers. It certainly did that, but it also described an evolutionary process that is surely to be found in every field of inquiry. This process is something he alluded to when referring to Derek Farrell’s description of the stages of development of EMDR: 1. Revolutionary; 2. Critical review; 3. Dismantling; 4. Acquisition of a more robust evidence base; 5. Adoption by national and international guidelines as effective evidence-based treatment for PTSD; 6. Increasing Evidence-Based Practice and Practice-Based Evidence for other mental health conditions which then inspires a new ‘revolutionary’ phase, thus bringing us back to the first phase to begin a new cycle.

Liebermann says he preferred to think of ‘Waves’ of EMDR rather than stages. If Shapiro’s work – and the ‘bible’ she left us with in the 3rd edition of her book (2018) – is the first Wave then, Lieberman says, ART, Flash, 3MDR, MOSAIC, EMDR 2.0 and Brainspotting might be considered the second Wave. We don’t know what the third Wave will look like but, he says, “how can we discuss this without excluding people with good ideas? Fundamentalism is not helpful, but nor is arbitrariness.”

Answering his final question, or grasping the horns of the dilemma if you will, may lie in our commitment to professionalism as therapists. Maintaining our curiosity, being present with our clients, reflecting on our practice, viewing ourselves as continually growing and evolving offers us the antidote to doing therapy by numbers. It safeguards us from falling foul of the urge to do rather than be.

It is so very easy to reach for the next technique that will provide the answer to the discomfort we might feel when our client ‘deviates’ from the path we expected them to follow. By prizing our experience, sitting uncomfortably with uncertainty, showing willingness to spend time reflecting on the work on which we and our clients collaborate; by asking ourselves how all this fits with the AIP model, we discover that EMDR is far richer and, in my experience at least, therapeutically effective for my clients (as well as for me).

Research (research, research, to quote Shapiro) should be our guide when ‘things go wrong’ or when we find the uncertainty too destabilising. It would not only help us to recognise the true innovations and improvements in practice but to avoid the versions of EMDR that, in Liebermann’s opinion, may be more indicative of narcissistic patterns than of genuine advances in practice.

References

Shapiro, F. (1989). Eye movement desensitization: a new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20, 211-217

Shapiro, F., (1991). Eye movement desensitization & reprocessing procedure: From EMD to EMD/R-a new treatment model for anxiety and related traumata. Behavior Therapist, 14, 133-135.

Hase, M., (2021). The structure of EMDR therapy: A guide for the therapist. Frontiers in Psychology. 12:660753.doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660753

Shapiro F. (2018) Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy: Basic Principles, Protocols and Procedures, 3rd Edition, Guilford Press.