Preventing and managing secondary trauma among supervisees

Ester Bar-Sade, Child and Adolescent EMDR Trainer and Clinical Psychologist and Ahuvi Oren, EMDR and Arts Therapist, gave a workshop on dealing with secondary trauma in supervision groups. Jessica Woolliscroft attended.

Given the year we have all had and the consequent ‘mental health pandemic’; I was keen to attend this workshop to see how I could best support overworked and vicariously traumatised supervisees. I was also curious to learn how to handle group supervision dynamics when secondary trauma is present. The speaker confirmed something many of us may have guessed; that it is novice therapists who are most at risk from secondary trauma (Ladany & Friedlander, 1995).

Novice therapists are more likely to work in the most challenging physical environments. For example, where there is competition for therapy rooms, higher status workers usually win out. Novice therapists will have the least professional power to influence their caseloads; and will have the least access to one-to-one supervision or personal therapy. They are desperately keen to get work experience and are motivated by altruism. This has the effect of ratcheting up unrealistic self-expectations and can lead to burnout if not sensitively handled.

Ester Bar-Sade and her co speaker, Ahuvi Oren, gave an excellent summary of different theories in the field, secondary trauma measures and the core competencies that can help us in improving our supervision practice. They also gave a detailed case study using a remote version of EMDR G-TEP. This workshop also, for me, raised some thorny questions about how best to organise supervision groups to address difficult feelings authentically without blurring the boundaries between supervision and personal therapy.

Noticing compassion

The workshop began with us being asked to notice our associations to the word “compassion”, which in itself was pretty revealing. We were then given a definition:

“Compassion is the concern for another’s suffering and the wish to alleviate that suffering”.

A touching video of toddlers hugging brought home how basic compassion is to human relationships. Bar-Sade described how helpers can be left with feelings of guilt and helplessness if they cannot alleviate another’s suffering. The video also brought home to me how profoundly we have been affected by the policy of social distancing and the consequent body hunger for the comfort of physical touch. Bar-Sade referred to the common term ‘burnout’ but then described three key concepts in the field seeking to explain burnout at more depth:

- Compassion fatigue CF (Figley 1995): an erosion of psychological resilience following repeated exposure to many difficult experiences at work. Figley notes it results as a combination of workplace, client and the helper’s personal factors leading to the “perfect storm”.

- Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) (Stamm 2005): the natural behaviours and emotions that result from knowing about a trauma experienced by somebody else.

- Vicarious Traumatisation VT (McCann and Pearlman 1990; Pearlman and Saakvitne 1995): this work revealed that VT is more complicated than emotional fatigue. VT changes the worker’s beliefs about the world. The client’s negative beliefs become consolidated into the therapists’ thinking. Some therapists experience moral distress when their deepest values are in conflict with the work they are required to do.

I was relieved to hear that the speaker herself found it almost impossible in practice to distinguish between these three concepts.

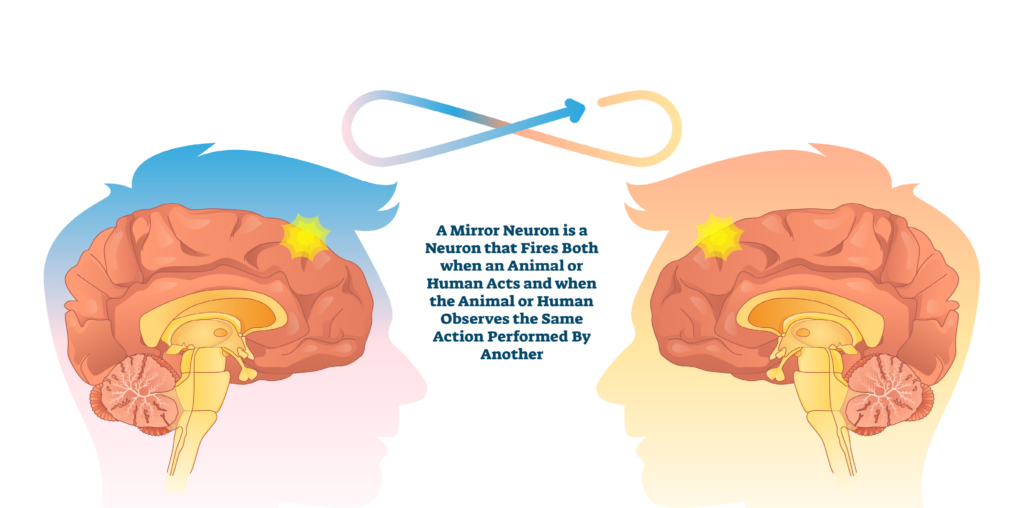

The workshop then made excellent use of video to illustrate the neurology of empathy. The Mirror Neuron System (MNS) was discovered during research that showed that the brains of laboratory monkeys watching a researcher move an arm, would ‘light up’ in the same areas of the neuronal network that would be activated if the monkey were to move its own arm (Jacoboni et al., 2003).

Figure 1. The Mirror Neuron System

The MNS seems to provide an explanation for empathy and also why empathy-based stress plays a part in STS, CF and VT (Rauvola et al., 2019). Therapists are at risk because they are exposed to the traumatic stories of their clients which activate their MNS; they are subjected to high professional expectations; and there is a limit to what they can achieve, all of which brings the possibility of failure and guilt. Bar-Sade made the excellent points that a good supportive workplace:

- Recognises these risks.

- Normalises the reactions instead of pathologising them.

- Manages expectations.

- Promotes resilience.

The workshop described a number of measures that can be used to identify STS, VT and CF:

- Professional Quality of Life Scale (ProQOL, 2009) measures Compassion Satisfaction and Compassion Fatigue and is freely available online. Made up of 30 items it has been used reliably for 12 years.

- STS scale Core Competencies for Supervisors is a very useful questionnaire for supervisors to assess their own knowledge and to ensure they are bringing an awareness of STS into their own supervision practice

- The Impact of Events Scale (IES), which all EMDR therapists will know about, can also be used to assess the impact of a workplace traumatic event.

Bar-Sade then subjected us to “The Bambi Test” – showing us the infamous scene from Disney’s Bambi when Bambi loses his mother. Would we feel compassion for Bambi? (I am still not sure if this was a genuine measure).

The workshop then helpfully listed the core competencies that supervisors should be using in their supervision practice. These were the ability to:

- Evaluate wellbeing.

- Identify supervisees’ negative self-appraisals; cognitive distortions and ineffective coping behaviours.

- Offer appropriate psychoeducation.

- Listen reflectively.

- Enhance supervisees’ strengths, self- awareness, self-regulatory skills.

- Normalise emotional responses to difficult situations.

- Support supervisees to make time for joyful experiences in life.

The remainder of the workshop then went into detail about the case study using video of the group and experiential exercises. The study used Elan Shapiro’s Remote G-Tep (2020) and the butterfly hug (Jarero et al., 2008) as the bilateral stimulation. The supervisees in the study were trainees working at a centre for young adults with developmental intellectual disabilities. It was a physically challenging environment as the centre had suffered from vandalism and the clients were also challenging, both physically and emotionally. The supervision group started by using the Four Elements relaxation and resourcing exercise. This was demonstrated beautifully by Ahiva Oren who encouraged all of us in the workshop to participate.

The supervisees in the case study would then be asked to picture and draw for themselves, on a piece of paper, an image representing a resource that made them feel good. They then had to select a target for processing related to a workplace stressor, to draw it and then assess the SUD level (0-10). Many of them felt anger about the chaos in the clinic where they were working. They then used butterfly hug as the BLS and drew a picture of what came up for them first. They would run through a number of sets of BLS drawing the new associations as they went. After a number of sets, the supervisees were invited to revisit their target and reassess the SUD level. They were then asked to visit a future in which they were coping well with the workplace stressor and to draw that, including positive words. There is a great use of the group to enhance resources and positive experiences. In the video shown, the supervision group were encouraged to sing and to show their drawings to each other. Bar-Sade noted that encouragement from the peer group of supervisees is a key element of the successful resourcing. She reminded us of the Mirror Neuron System, which would be activated by others behaving joyfully and happily.

Boundaries

One key area that arose in the Q & A was that of boundaries. How, it was asked, did the supervisor ensure that boundaries between workplace supervision and personal therapy were maintained? Bar-Sade replied that she always held in mind three key criteria for using G-Tep in supervision:

- Has the supervisee been activated by a current workplace trigger and can supervision offer a beneficial experience?

- Is there a good enough working alliance between the supervisee and the supervisor?

- Are there underlying feeder memories relating to the supervisees personal material? In this case, she would refer the supervisee to their personal therapy.

I enjoyed this workshop and intend to read further about the core competencies for supervisors. It was very well presented, using experiential exercises, video and a generous and well organised handout which included the ProQOL. However, I was left with an uneasy feeling about the ethics of combining G-TEP with supervision. I am loathe to criticise anything that could alleviate the burden of workplace stress, but despite the response to the question about boundaries, I personally feel there is a real issue about the blurring of personal therapy and supervision in a group. This brings me to the point raised at the beginning of my report, in which research shows that novice therapists are most likely to be traumatised in the workplace. Bearing the power dynamics in mind, my concerns are these:

- How easy would it be for a trainee psychologist to refuse to participate in a G-TEP supervision exercise, given the power dynamics, peer pressure and the need for work experience, references and ongoing supervision and training with the supervisor?

- Is it possible that there are cultural differences between Israel, the UK and other countries in terms of how willing supervisees might be to share personal material with their peers, or even to sing along in a group setting?

I do think it would be possible to design something like this in a way that addresses and removes the boundary issues. Firstly, the G-TEP groups could be a voluntary addition to existing supervision. Secondly, the G-TEP groups would need to be completely confidential. Thirdly the G-TEP facilitator would need to be separate completely from the workplace setting with no dual relationships. Fourthly, the G-TEP group would benefit from peer support even more if its members were drawn from different workplaces. This would enhance confidentiality and make the group a safer place.

Ester Bar–Sade is keen to gather more data to support this way of working and would welcome contact from EMDR colleagues wanting to set up similar group supervision studies.

Useful Resources.

Using the Secondary Traumatic Stress Core Competencies in Trauma-Informed Supervision Introduction How to Use the STS Supervisor Competency Tool https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/factsheet/using_the_secondary_traumatic_stress_core_competencies_in_traumainformed_supervision.pdf

Guidelines for a Vicarious Trauma-Informed Organization: Supervision https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/media/document/sup_in_a_vt_i nformed_organization-508.pdf

References

Figley, C. R. (Ed.) (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

Ladany, N., Ellis, M. V., & Friedlander, M. L. (1999). The supervisory working alliance, trainee self-efficacy, and satisfaction. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(4), 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556- 6676.1999.tb02472.x

Pearlman, L. & Saakvitne, K. (1995). Trauma and the Therapist. New York, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc

Rauvola.R.S., Vega,D.M. and Lavigne.K.N., (2019). Compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization: A qualitative review and research agenda.Occupational Health Science volume 3, pp297–336 (2019)

Shapiro, E. (2007). ‘The 4 Elements Exercise’, Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2, 113-115

Shapiro, E. (2020). Group-traumatic episode protocol remote individual & selfcare protocol (G-TEP RISC). In M. Luber’s (Ed.), EMDR resources in the era of COVID-19 (pp. 160-161).

Stamm, B.H. (2005). The ProQOL Manual. The Professional Quality of Life Scale: Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Compassion Fatigue/Secondary Trauma Scales. Lutherville, MD: Sidran Press.