Online EMDR works – it’s official!

The results of a service evaluation conducted between May and December 2020 shows that online EMDR is effective. Summarising the results of the survey at the Annual Conference on Friday 21 March, Naomi Fisher, Iain McGowan and Justin Havens concluded that online EMDR is here to stay and confirmed that a larger scale trial was underway and would report results in the near future.

The evaluation sought to answer two simple questions: first whether online EMDR is effective and whether outcomes depended on the level of the therapist’s EMDR experience. It did not seek to influence the clinical practice of those taking part but merely an evaluation of what is already happening in online EMDR. Of the 140 therapists registering interest, 33 provided data on 93 clients. Forty percent of the clients presented with complex PTSD, 20 percent with simple PTSD. Others had depression, anxiety, OCD and phobias. Only one came purely for treatment pertaining to COVID-related problems.

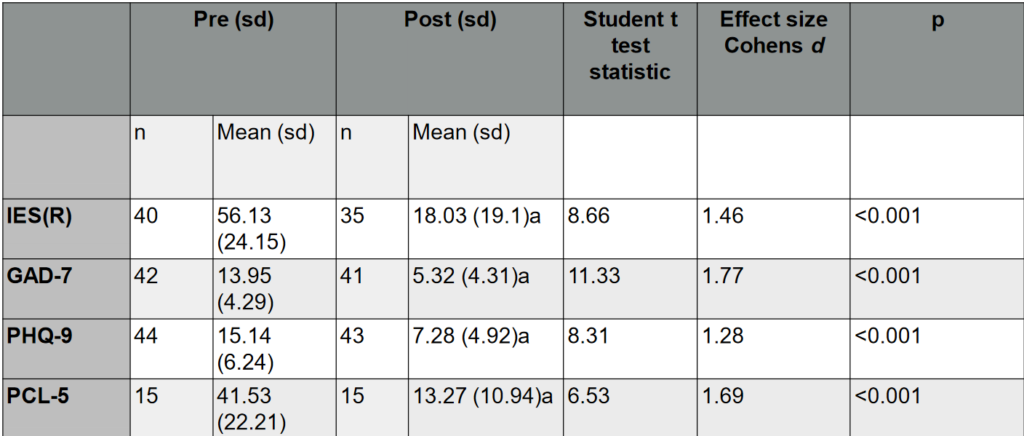

Therapists used one or more of the following measures: GAD-7, PHQ-9, PCL-5 and SUDs scores. The survey did not specify that particular outcome measures had to be used. Despite this, the survey found that there was significant reduction of symptoms on all measures reported (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Results of the service evaluation

The results suggest that online EMDR can reduce symptoms of PTSD as well as of anxiety and depression. There was no evidence to suggest that the level of therapist experience influenced outcomes. Havens pointed out that the study could say nothing about how online therapy compared with in-person therapy, or with other therapies. Nor could it rule out the possibility of gatekeeper bias – that is, the reporting of only positive outcomes. However, it did show that reduction of symptoms occurred across all ages, gender and clinical presentations.

The findings are encouraging and the team announced that larger scale trials are already in progress. A paper has been submitted to the journal BMC Psychiatry and the E. Anglia Regional Group and Sheffield University are planning a joint project to survey therapist and client experiences of online EMDR.

We can expect to read about many more evaluations of online therapy in the future as the experience of working with the constraints of a pandemic has led not just to enormous creativity but to greater flexibility in the delivery of therapy. Indeed, one of the presenters, Naomi Fisher, recently published a comprehensive paper on the practicalities of delivering EMDR therapy online (Fisher, 2021)1. The paper considers the establishment of safety and the therapeutic relationship, assessment and case formulation, preparation and stabilisation, trauma processing, complications and the three-pronged approach. Under each of those headings, Fisher considers the differences with online work and how to mitigate unforeseen difficulties.

One of the key messages implied in Fisher’s helpful paper is that clinicians must fully embrace online work, accepting that it is equally effective as in-person work and, sometimes, more effective. This means taking the time to bring clients on board with this new way of receiving therapy and accepting responsibility for creating a therapeutic virtual environment.

Barriers to online therapy

These messages were reinforced in Ben Wright’s presentation which provided patient experiences, clinical outcomes in the NHS Trust where Wright works. The data were collected from four IAPT services in Bedfordshire, Tower Hamlets, Richmond and Newham. One of the most interesting findings concerned barriers to accessing therapy. Although 96 percent of households had access to the internet, two-thirds of the remainder disregard the internet because believed it offered insufficient benefits.

Wright’s data showed on the contrary that online working provided the opportunity for greater engagement with therapy and continued effectiveness, although each service needed to go through a transition period in which they become familiarised with the benefits of virtual working. Greater engagement was found to be across the board; comparing pre-COVID and post-COVID referrals, Wright found that 10 percent more people went into assessment and treatment within the four services studied. Attendance improved from 73 percent to 77 percent and, since the average number of sessions is linked to recovery rate, this meant increased recovery. Wright said “it’s a reasonable hypothesis to suggest that virtual working makes therapy more accessible and when people turn up to appointments they generally get better”.

Interestingly, whereas the effectiveness of online EMDR for PTSD significantly improved from 45 percent to 58 percent, the effectiveness of TF-CBT remained virtually unchanged.

Wright concluded with the following tips based on his own and his colleagues’ experience:

- It is the clinician’s responsibility to create an effective environment that extends to virtual care and that clinicians should not accept an anti-therapeutic virtual environment.

- Digital enablement of clients is a legitimate clinical activity.

- It is important to maintain therapist professionalism and confidence.

References

-

Fisher, N. Using EMDR to treat clients remotely, Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, Volume 15, Number 1, p73