Deep Brain Reorienting: unlocking body memory

Abrar Hussain was fascinated by Dr Frank Corrigan’s talk on Deep Brain Reorienting (DBR) and the role of the midbrain in processing trauma. He sees EMDR as a particularly appropriate in processing trauma that is somatically stored.

As the frontiers of our neurological understanding expand, so does the richness of our toolboxes and skills sets within our clinical work. Dr Frank Corrigan’s presentation on the concept of Deep Brain Reorienting and the neuroanatomy that underpins it, helped me to understand how scientific discovery can be practically applied in everyday practice.

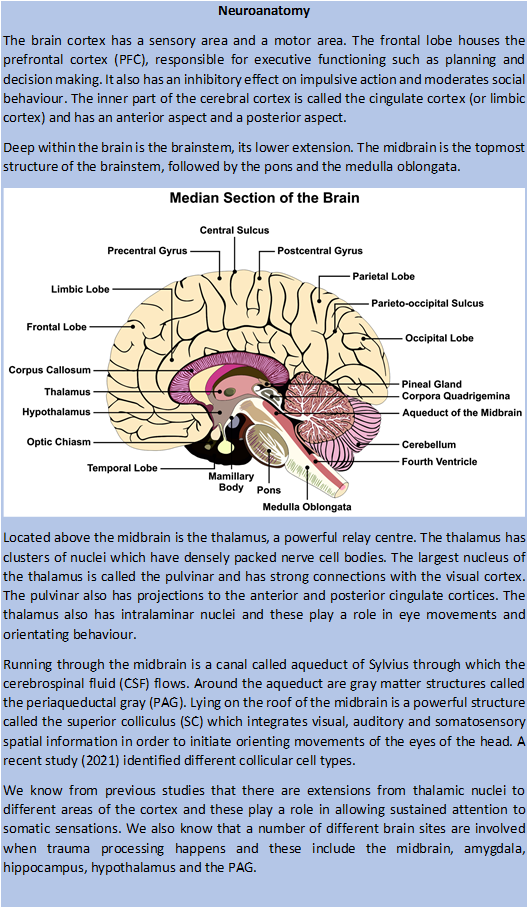

Neurobiology highlights the somatic aspect of trauma work and underpins the importance of body awareness in trauma psychotherapy. Being aware of the brain’s structure and function enables therapists to pursue an evidence-based approach as the clinical work will be underpinned by proven neurological considerations (see the Box giving an overview of the relevant neuroanatomy). Further it gives patients the confidence that the therapy they are having has a sound grounding in scientific principles

Somatic trauma storage

Corrigan explained that “body awareness of the trauma memory states” is a concept common to all body-based therapy modalities. The resolution of trauma involves thalamocortical processing, which binds together memory, visceral sensations, thoughts and other components of traumatic experiences. The clinical importance of processing all these components and visceral/somatic symptoms in particular cannot be understated as traumatic memories are not necessarily fully accessible to verbal recall. In other words, not paying attention to somatic signals may not fully resolve the trauma. In my view, this also makes EMDR unique when compared to other psychotherapies in which words and language are so heavily relied upon.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) performs risk assessments when danger is distant; this can help the person plan and organise the response to the oncoming danger. However, the PAG takes over when threat is close. The periaqueductal gray (PAG) can trigger an affective response as well as mount a defence (in the form of a fight, flight or freeze response). This affective involvement is complex; it extends beyond just fear and includes rage, shame, abandonment and distress. Clinicians need to be aware of this and so be prepared to support the patient in navigating complex and confusing emotions. It is important to remember that patients may access these new feelings for the first time during trauma work and that this can be difficult and potentially destabilising.

Application in processing

EMDR causes neurophysiological shifts and, as different components of the trauma are accessed and processed, different parts of the brain come into play. The inherent healing power of the brain accounts partly for how EMDR can sometimes jumpstart this process and allow for the trauma to continue to be assimilated and made sense of in between sessions.

During trauma processing, there is signal transmission from the posterior to anterior cingulate cortex. The PFC–PAG axis plays an important role in organising the threat response and EMDR taps into this. Any shift of activity from the PFC to PAG can cause emotional upset, abreaction and dissociation. This mechanism underpins the importance of preparatory work, grounding and keeping the processing within the window of affect tolerance. Ensuring the patient is grounded means they are in the present and therefore less likely to dissociate or experience overwhelm.

The superior colliculus (SC) and its interactions similarly play a crucial role in trauma processing. The superficial layers of the SC interact with the pulvinar of the thalamus. This interaction creates a fast pathway and detects any visual threat (such as an angry face or a snake). The intermediate layers of the SC are involved in perceiving auditory and somatosensory stimuli. The deeper layers help in preparing for the threat and are implicated in the muscle tone of the forehead, neck and eye muscles.

Working with a DBR lens

DBR appears to offer therapists a gentler mode of getting into the trauma work and reducing the risk of emotional overwhelm.

The perception of danger makes an individual to prepare for movement. Before themovement can take place, there is a pattern of pre-movement tension; this can happen even before any affect is generated. This “pre-affective bracing” is the shock that hits before emotions are felt in response to a traumatic event; it happens before a defence response can be mounted and can be difficult to pick up. This may be in the form of a physical sensation (butterflies in the stomach, chest tightness, pain etc) and will usually be a unique response for each individual. As therapists, it is therefore important to be aware of this and actively look for such signs. The associated “orienting tension” is the core focus in Deep Brain Reorienting (DBR) and with training and practice, it may be possible to recognise this. The approach safeguards against emotional overwhelm and dissociative switches as deepening awareness into the orienting tension provides an anchor. This grounds the patient and protects them from deviating from the present.

I found the concept of DBR helpful and hope to learn more about it in order to apply it in my clinical practice. Being able to talk to patients about the neuroanatomical underpinnings and relate it to the clinical work is likely to help them in their journey towards healing and growth.