More evidence for intensive EMDR in complex PTSD

Professor Ad de Jongh’s presentation of the intensive therapy programme offered at Psytrec in The Netherlands raised many questions for Jessica Woolliscroft.

This work is now famous in the traumatology world, not lease because it seems to fly in the face of everything we are taught about how to deliver trauma therapy. The importance of using a phased approach with plenty of stabilisation, particularly for clients with complex PTSD, has been widely accepted as necessary and good practice. It is also widely accepted that patients diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder (DID) or borderline personality disorder (BPD) need to have their trauma therapy adapted, to take account of the split-off parts of the dissociative patient, or to build a safe enough relationship of trust and boundaries to contain the BPD patient. But no, not according to this presentation by Professor Ad de Jongh. Patients with dissociative and borderline presentations receiving inpatient treatment at Psytrec for their CPTSD symptoms, do very well in a regime with minimal stabilisation, and no consistent therapeutic relationship. In fact, at Psytrec in The Netherlands where De Jongh is based, the therapists treat the patients on a rotation. How was this possible? I was curious to learn more and was full of questions.

De Jongh began by referring to a discussion in the EMDR field as to whether stabilisation was really necessary as a part of treatment, and also whether it was safe to treat patients more frequently than once a week? A breakthrough study by Anke Ehlers (2014) showed that treating patients once a day over two weeks was as effective as treating them weekly over three months. It was not ‘better’ but it was more efficient; patients could get back to work faster and their lives improved more quickly, both of which are important.

The Ehlers study used trauma focused CBT (TFCBT) for single event traumas. De Jongh wanted to know what would happen if EMDR was used for complex PTSD (CPTSD) and offering several sessions a day. Ehlers found that: a one-week treatment with one session a day was just as effective as a once-a-week treatment lasting three months; after 7 days, 73% of patients no longer had PTSD; there was no increase in drop-out or symptom worsening.

In 2015, De Jongh collaborated with a colleague, Agnes Van Minnen who is an expert in providing exposure treatments. They set up Psytrec, an inpatient PTSD clinic offering intensive treatments over two weeks (two lots of four days).

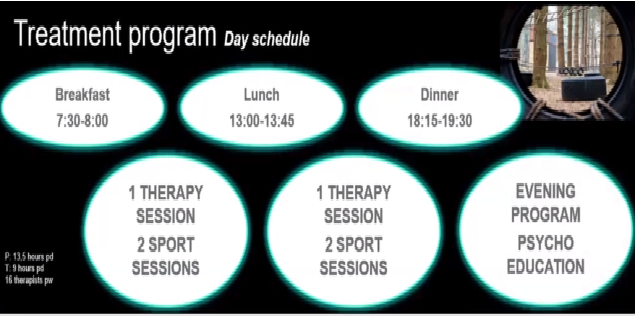

Figure 1: The typical Psytrec treatment regime

The therapy involved two sessions of 90-minute therapy, beginning with exposure therapy and then moving to EMDR. Therapy sessions were interspersed with a lot of physical activities, sports mainly (Figure 1). This was to offer patients something to do between sessions, filling their time so they would not ruminate. De Jongh is currently completing a randomised control trial to see if groups with no sport show different outcomes to groups with sport. Meals were eaten together and in the evening there was a two-hour psychoeducation session.

The patients were typically people who had been in various forms of treatment for 15 years, with no significant improvement. They had experienced multiple traumas leading to severe PTSD involving typically more than five memories of a Criterion A event. (Criterion A events are life-threatening to oneself or to others). Psytrec had virtually no exclusion criteria and accepted patients with BPD and DID diagnoses.

The presenting issues of patients in this study at Psytrec were:

- suicidal thoughts (73%)

- co morbid depression (89%)

- dissociation (26%)

- experienced sexual abuse (75%)

- experienced sexual abuse before age 12 (45%)

- experienced physical violence (79%)

The clinic was accepting approximately 120 patients a month. The radical departure from normal treatment models was the introduction of therapist rotation. A patient could see 10-16 different therapists for treatment sessions in the course of their stay. De Jongh noted that the advantages of therapist rotation were:

- Shared responsibility and less burden on individual therapists

- Opportunity to learn from those with more clinical experience

- Less drift away from the model, so more faithful to the protocols

- Opportunity to experience a wider variety of patient presentations

De Jongh said that, counterintuitively, patients reported preferringthe therapist rotation model to seeing only one therapist. Moreover, amazingly there was a very low dropout rate of only 3%, most of which were sporting accidents!

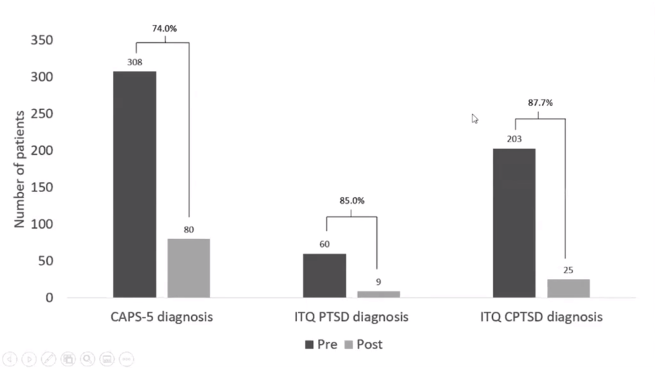

Figure 2: results of the study comparing diagnoses before and after treatment.

Using different measures for diagnosing CPTSD, the study showed reductions in the diagnosis of 74-87% (Figure 2).

One interesting finding of this study was that patients assessed as having a dissociative disorder also responded well to the programme. An astonishing aspect of the programme was that of 35 patients diagnosed with BPD before the treatment, 33% no longer met the criteria for BPD after treatment. They suffered no negative side effects and there were no drop outs.

A meta-analysis by Slotema et al. (2020) of all studies exploring the effect of treatment for PTSD on the severity of BPD symptoms showed that the Psytrec programme had the most effective results. This has led to a very large study to look at the treatment of BPD using this approach with a 12-month follow up.

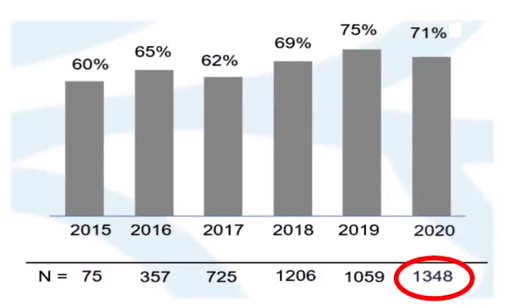

De Jongh then showed the clinic’s results from 2015-2020 (see Figure 3) and drew our attention to the very large numbers of patients being treated using this model. As he put it, this is not a small study with a handful of patients. This is hundreds of successful outcomes in patients who had not responded to other approaches.

Figure 3: Psytrec’s record of CPTSD patients treated 2015-2020 and resulting loss of diagnoses

As this talk was part of a wider symposium looking at intensive treatments for children and adolescents and for families, there was very little time to ask questions. However, In response to two questions, De Jongh said he had not experienced any difference at all between patients being treated for CPTSD due to combat trauma and those with trauma as a result of childhood sexual abuse. I personally would have loved to drill down into this more, but there was no time. De Jongh ended with the interesting comment that: “Avoidance is a huge issue, and focusing on the trauma is paramount”.

He said that therapists use Flashforward to process patients’ catastrophic fears of the treatment/trauma itself, and that is how they deal with the avoidance and defensiveness.

This study is so impressive and raises so many questions about how therapy is normally delivered. After the conference I reflected myself upon whether I would want to go through such a programme. As I do need to lose a few pounds, the idea of being forced to exercise everyday did appeal to me. I did feel a strong aversion to seeing a different therapist for every session, though. Out of interest I raised this question with a handful of EMDR colleagues. Although everyone was impressed by the work, no one I asked wanted to be treated by a rotation of therapists. However, the results do speak volumes. De Jongh’s colleague, Petra Fokkema, reported from her similar programme with adolescents, that only one teenage girl had strongly objected to the therapist rotation model, but this same girl showed the greatest improvement in her symptoms.

This study does raise the question of how much do we and our supervisees get pulled into our clients’ avoidance patterns. How do we collude? If we were not affected powerfully by the relational dynamic, and working in a therapist rotation model, would we be less avoidant and more willing to firmly challenge the defences of our clients? I would have loved to ask questions such as:

- How do the teams deal with dissociated parts, clients who refuse to engage, clients that try to split the teams in order to avoid and clients that resist recovery because of secondary relational gains?

- Have the patients received therapy before coming to the clinic?

- Was their therapy prior to arriving at Psyctrec EMDR or other modalities that do not have an evidence base for effectiveness?

- What follow ups have been done on these clients?

- Do they stay in the nonclinical range six months after leaving the clinic?

- Can RCTs be done comparing therapists rotation with same therapist model?

I guess the deeper question for me is, whether these clients are responding so well because they are finally being offered a treatment that is specifically designed to treat trauma, i.e. EMDR. Could it be that their recovery is solely due to their receiving EMDR rather than all the other aspects of the programme? Would the results be enhanced if they had the same therapist and a stabilisation phase? Long term follow-up of these clients would be very interesting. Nor should we overlook the likely powerful effect of being in such an intense setting with an enthusiastic team that is led by a charismatic clinician.

I would love to visit this clinic to observe the work itself as it challenges so many of our preconceptions. I would need to invest in some new workout gear though.

References

Bongaerts, H., Van Minnen, A., de Jongh, A. ( 2020) Intensive EMDR to treat patients with Complex Post traumatic Stress Disorder: A case Series. Journal of EMDR practice and Research Vol 11 Issue 2

Slotema, C. W., Wilhelmus, B., Arends, L.R., Franken, I. H. A. (2020) Psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its efficacy and safety. European Journal Psychotraumatology Sept 16: 11(1).